Effeminacy Is Not A Vice

Except when you're speaking improperly. (We should stop speaking improperly.)

Cultural “Effeminacy”

The New Oxford English Dictionary defines effeminacy as “the quality in a man of having characteristics and ways of behaving traditionally associated with women and regarded as inappropriate for a man”. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines effeminacy as “having feminine qualities untypical of a man; not manly in appearance or manner”. And the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary defines effeminacy as “the state of behaving, looking like, or having qualities similar to a woman”. This is the ordinary sense in which lace and pretty flowers and painted nails and gentleness tend to be culturally more associated with women (whether that association renders it inappropriate or merely untypical for a man is less essential). This is the sense in which we have feminine stereotypes – just as we have masculine stereotypes like aggression and beards and stoicism and hunting and cigars, and even the equivalent opposite term mannishness, which might be applied to women having characteristics or ways of behaving that are traditionally or stereotypically associated with men.

There is nothing particularly wrong with any of these terms or definitions. However, there is a great deal that can go wrong – very quickly and very badly – when we mix in poor or problematic ideas about which manners, appearances, characteristics, and behaviors are or should be associated with women. For example, this is the same (deeply unserious) sense in which Taylor Marshall once labeled gingerbread house competitions as “effeminate”, and Jesse Watters similarly proposed that men should not drink from straws “and one of the reasons you don’t drink from a straw is the way your lips purse: it’s very effeminate”. Simply establish (or take for granted) some alleged association of a given trait or behavior with women – clothing, accessories, cosmetics, hair style, general demeanor – and sure, calling a man “effeminate” may well be definitionally correct in the intended English-language sense, full stop.

But if we are using the word in that sense, then there is plainly nothing inherently materially sinful about “effeminacy”. There is a reason you will not find this concept anywhere in the Catechism of the Catholic Church: it’s this definition of the term reflects little more than a fact (or simply an opinion) regarding the prevailing cultural stereotypes for which roles, behaviors, and appearances tend to be associated with a social perception or sense of what is “masculine” or “feminine”. And stereotypes or associations of this sort – which are inherently malleable and changeable according to time and place – are not a coherent basis for the formation of an authentic moral judgment. On the contrary, we must be cautious, as Pope Francis reminded us:

But it is also true that masculinity and femininity are not rigid categories. It is possible, for example, that a husband’s way of being masculine can be flexibly adapted to the wife’s work schedule. Taking on domestic chores or some aspects of raising children does not make him any less masculine or imply failure, irresponsibility or cause for shame. Children have to be helped to accept as normal such healthy “exchanges” which do not diminish the dignity of the father figure. A rigid approach turns into an overaccentuation of the masculine or feminine, and does not help children and young people to appreciate the genuine reciprocity incarnate in the real conditions of matrimony. Such rigidity, in turn, can hinder the development of an individual’s abilities, to the point of leading him or her to think, for example, that it is not really masculine to cultivate art or dance, or not very feminine to exercise leadership. (Amoris Laetitia, n. 286)

Cultural stereotypes governing our perception of “masculinity” and “femininity” may be real, but they are never inherently beyond all questioning. On the contrary, gender stereotypes must be approached and generally held only with great caution, lest they be permitted to devolve into excessively rigid categories that are harmful to individual persons, and that oppose the truth about how men and women can or should be free to authentically express themselves in society, through qualities and behaviors and mannerisms that do not actually violate the moral law in any coherent sense. The truth is that the “social violation” of breaking merely customary associations governing the “masculine” and “feminine” does not inherently or properly correspond to any objective material sin (with all due allowance for questions about prudence).

This ordinary definition of “effeminacy” – one rooted fundamentally in the cultural or social perception of so-called masculine or feminine qualities or behaviors – is not something inherently bad. It can be useful, or simply reflective of a real custom embedded in the culture. But it can also be dangerous, if we hold it too tightly, or misunderstand something required by custom as something required by nature. And it can be something that we are justified in resisting (or even positively obliged to dismantle and reform) if it becomes too rigid, and creates oppressive structures, or infringes upon legitimate modes of expression that do not actually violate any moral law. For lack of a better term, we can refer to this as effeminacy “type A”.

And effeminacy-A is not a vice.

Moral “Effeminacy”

So far, so boring. But there is a second, radically different concept of effeminacy that is frequently cited by theological speakers, which comes to us from the popular English translations of Aquinas. Specifically, in an article on a vice opposed to the virtue of perseverance, Thomas Aquinas explains (Summa Theologiae II-II, Q.138, A.1):

…perseverance is deserving of praise because thereby one who does not forsake a good on account of long endurance of difficulties and toils: and it is directly opposed to this, seemingly, for a person to be ready to forsake a good on account of difficulties which they cannot endure. This is what we understand by softness, because a thing is said to be ‘soft’ if it readily yields to the touch. Now a thing is not declared to be soft through yielding to a heavy blow, for walls yield to the battering-ram. Wherefore a person is not said to be soft if they yield to heavy blows. […] Wherefore, according to the Philosopher (Ethic. vii, 7), properly speaking a soft person is one who withdraws from good on account of sorrow caused by lack of pleasure, yielding as it were to a weak motion.

If you’re now wondering okay, wait, what does that have to do with effeminacy, then congratulations – your instinct is absolutely correct – but bear with me.

First, let’s understand that the Latin terms Aquinas uses throughout this article are mollities (movableness, pliability, flexibility, suppleness, softness) and mollis (soft, mild, weak or easily movable, pliant, flexible, supple, tender, delicate, gentle, pleasant). And then second, let’s pay careful attention to what is being described: because this sort of pliability or weakness or softness – in the sense of moral flexibility (readily yielding to temptations to abandon a difficult moral good, simply because it is more pleasant to give in and let bodily pleasure take priority) – is quite obviously opposed to the virtue of perseverance, and obviously makes sense to characterize as a vice (above all, when it becomes a habitual disposition or quality of a person’s character).

Now, let’s revisit the text, because I have something to confess: the translation I used above is my own rehabilitation of the common English translation, but not how you will find the text most commonly rendered. Feel free to consult the Latin and English translation side-by-side for yourself, because this is where our problems begin:

…perseverance is deserving of praise because thereby a man does not forsake a good on account of long endurance of difficulties and toils: and it is directly opposed to this, seemingly, for a man to be ready to forsake a good on account of difficulties which he cannot endure. This is what we understand by effeminacy [mollitiei], because a thing is said to be ‘soft’ [molle] if it readily yields to the touch. Now a thing is not declared to be soft through yielding to a heavy blow, for walls yield to the battering-ram. Wherefore a man is not said to be effeminate if he yields to heavy blows. Hence the Philosopher says (Ethic. vii, 7) that “it is no wonder, if a person is overcome by strong and overwhelming pleasures or sorrows; but he is to be pardoned if he struggles against them.” […] Wherefore, according to the Philosopher (Ethic. vii, 7), properly speaking an effeminate [mollis] man is one who withdraws from good on account of sorrow caused by lack of pleasure, yielding as it were to a weak motion.

The common decision to render the Latin words mollities and mollis into the English effeminate and effeminacy is… well, it’s very problematic: because the only way you can get to that translation is through an acceptance of weakness being a distinctly feminine quality. And at root, that is not at all what Aquinas is actually arguing, or attempting to convey. There is a reason you will not find Aquinas discussing an opposite vice of “mannishness” for women: because superficial appearances and mannerisms have nothing to do with a vice opposed to perseverance. He is not speaking about culturally gender-coded appearances or stereotypical mannerisms. Rather, he speaks of moral softness being opposed to perseverance, and not about femininity or masculinity. Thus another popular English translation hosted online by New Advent goes out of its way to highlight this particular translation issue in bright red text, at the top of the article – and rightly so, lest the English reader immediately misunderstand the term.

But more than this: not once does Aquinas actually refer to men in the main body of his answer, at all. Again, please review the Latin text for yourself, and compare it to the English translation: you will find neither the Latin word for the specifically male person (vir, viri) nor the Latin word for human or mankind (homo, hominis) in his main response, as the English translation would suggest. Rather, this is another common translation choice: to render the implicit pronouns and generic “anyone” (aliquis) into English as “a man” and “he”, rather than as “a person” or “one”. And sure, normally this might not be a critical issue. But when it is combined with the misogynistic-adjacent instinct to render the Latin mollis as effeminacy, then we have compounded the gravity of this translation problem for the English reader. And this immediately fuels grave misunderstandings: for now the Angelic Doctor appears to claim that “the effeminate man” (i.e. the biological male exhibiting mannerisms, appearances, characteristics, or behaviors that are considered feminine, due to being culturally associated with women) exhibits a vice opposed to authentic virtue, when in truth that is laughably far from the actual meaning of the text. Aquinas is not describing a moral vice that pertains uniquely to male persons having “feminine” qualities. He is describing one very specific moral quality – the softness opposed to perseverance – which is in fact a universal vice that can equally afflict both men and women.

But unfortunately, this use of effeminacy as a translation for mollities is quite deeply rooted, to such a degree that – if only as a practical matter – we have to deal with it. So for lack of a better term, we can refer to this as effeminacy “type B”.

And effeminacy-B is absolutely a vice.

Thomistic Troubles

How did we get here? How did we end up with one word “effeminacy” being used to describe these two concepts? Answering this question requires us to unpack a deeper problem: Aquinas’ uncritical acceptance of ancient Aristotelian biology.

Now, I will not be exploring or unpacking that issue at length here. If you are somehow not already familiar with the basic problem (as it frequently comes up in connection with how Aquinas thought about the Immaculate Conception), then this essay provides a charitable analysis that does not shy away from summarizing the many problematic premises and conclusions of Aristotelian biology, including (of great relevance for us now) the idea that: “Woman, by nature, would have a weak disposition because she would not realize the same degree of vital heat as the male.”

This is… again, deeply problematic, for many reasons. But we must recognize this root of the problem, in order to understand and appreciate how it silently shapes the arguments that Aquinas adopts and advances when discussing the nature of women. Consider, for instance, his claim in Summa Theologiae II-II, Q.156, A.1:

Reply Obj. 1: …since woman, as regards the body, has a weak temperament, the result is that for the most part, whatever she holds to, she holds to it weakly; although in rare cases the opposite occurs, according to Prov. 31:10, ‘Who shall find a valiant woman?’ And since small and weak things ‘are accounted as though they were not’ the Philosopher speaks of women as though they had not the firm judgment of reason, although the contrary happens in some women. Hence he states that ‘we do not describe women as being continent, because they are vacillating’ through being unstable of reason, and ‘are easily led’ so that they follow their passions readily.

Again, Aristotle is quite wrong about this. However… the moment you understand how seamlessly these views about the nature of women flow from Aristotelian biology of the male and female sexes, in that same moment you can also see the intuitive connection that is naturally being drawn between stereotypical feminine weakness (vacillating, unstable, not holding firm in the judgment of reason but easily movable by emotion) and the specific vice contrary to perseverance that is being described under the heading of effeminacy-B (quickly yielding to bodily desires, emotions, and temptations toward pleasure, rather than holding firm in the pursuit of a difficult moral good).

And thus also, the moment that we abandon Aristotelian biology regarding the male and female sexes, in that same moment we can also see how we must be forced to acknowledge that the connection historically drawn between these two things is no longer reliable. When as we reject the vision of ancient Aristotelian biology viewing women as “defective and misbegotten, for the active force in the male seed tends to the production of a perfect likeness in the masculine sex” (Summa Theologiae I, Q.92, A.1), then we undermine any natural link between effeminacy-A and effeminacy-B. The “weak” feminine temperament can no longer be rooted in any credible element of her biological nature, and thus immediately devolves into (at best) a fragile connection rooted only in the stereotype of women having inherently emotional temperaments. This is, quite simply, not something we actually have any need to defend.

Before moving on, there is a bit more we must address. For, returning to Aquinas’ article on the “effeminacy” opposed to perseverance (Summa Theologiae II-II, Q.138, A.1), we find that he also leans into that same Aristotelian framework on this occasion – also indirectly highlighting a (rather strained) connection to homosexuality:

Objection 1: It seems that effeminacy [mollities] is not opposed to perseverance. For a gloss on 1 Corinthians 6:9-10, “neither adulterers, nor the effeminate [molles], nor liers with mankind [masculorum concubitores]” expounds the text thus: “effeminate [molles], that is obscene, given to womanly submissiveness [muliebria patientes].’ But this is opposed to chastity. Therefore [it seems] effeminacy is not a vice opposed to perseverance.

Now we must immediately acknowledge (although again, I will not be exploring this tangent in-depth) that Saint Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians was absolutely not originally written in the Latin language [molles and masculorum concubitores], but rather in Greek [malakoi and arsenokoitai]. And this is not an insignificant issue: because the actual meaning of those Greek terms is a subject of much scholarly debate, and therefore defending the choice to translate the Greek malakoi into the Latin molles (and later again into the English effeminacy) requires a rather confident conviction on the intended meaning of the Greek. [For some accessible entry points into this debate, see this essay by Bridget Eileen Rivera, this overview by Kathy Baldock, this video by Dan McClellan, and a pair of reflections here and here by Ron Belgau.]

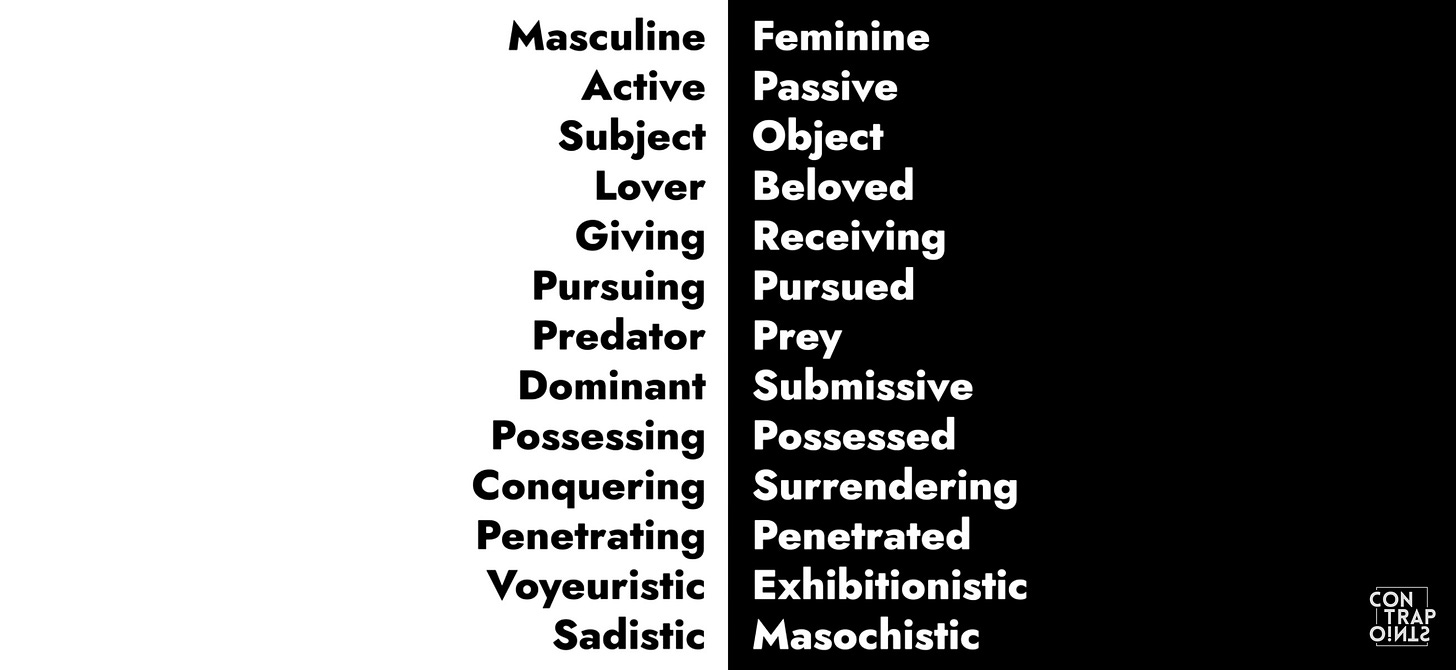

Here it will be sufficient to understand that one school of interpretation views the term malakoi in 1 Corinthians as more narrowly referring to those who engage in the “passive” or “receptive” homosexual sex act (i.e. an action that certainly could from a certain point of view be taken as the more “feminine” role), in contrast with the “active” or “penetrative” role that is listed separately as arsenokoitai (at least on this reading of the text). And if this is correct, it will follow – contrary to what many people claim – that the “effeminate” sin molles in 1 Corinthians 6:9-10 does not actually refer to either stereotypically “womanly” mannerisms or appearances (effeminacy-A) or to the vice opposed to perseverance (effeminacy-B), but instead only to a “womanly” male sexual role (which we might call “effeminacy C”) that bears only a partial resonance to the broad sense of effeminacy-A, if you tilt your head and squint at it.

Another school of interpretation, however, tends to view the term malakoi more broadly: still absolutely bearing some cultural link to the “submissive” homosexual role, but simultaneously carrying a stronger link to the broad vision of effeminacy-B: morally weak, easily driven by desires for pleasure and lust, not exercising any sort of virtuous strength to resist the impulses to live decadently and indulge. And – this is the crucial link – when that broad vision of malakoi is viewed from within an Aristotelian framework that would biologically link those characteristics to a temperament allegedly by nature associated with women (effeminacy-A), then the emerging Latin molles and English effeminacy translations for malakoi start to make a whole lot of sense… even if we should today reject the premises that seamlessly led to that translation.

Having explained all of this, as preliminary groundwork for what you are now about to read, let’s now examine how Aquinas (here using only the Latin text, not addressing the original Greek) proceeds to respond to the objection:

Reply Obj. 1: This effeminacy [mollities] is caused in two ways. In one way, by custom: for where someone [aliquis] is accustomed to enjoy pleasures, it is more difficult for them to endure the lack of them. In another way, by natural disposition, because, to wit, their mind is less persevering through the frailty of their temperament. This is how women are compared to men [hoc modo comparantur feminae ad masculos], as the Philosopher says (Ethic. vii, 7): wherefore those who are passively sodomitical [muliebria patiuntur] are said to be effeminate [molles], being womanish [quasi muliebres effecti] themselves, as it were.

Again, this is just… really. not. great. But given an Aristotelian biological premise, it does makes sense that all of these layers would blend and blur together under one broad heading of “effeminacy”, not requiring any rigid distinction. For on this view, the “weak” vice does appear to have an intuitive link both primarily to the alleged natural temperaments of women, and secondarily to the “passive” sexual action that is quasi-feminine. But no matter how understandable this dual link to femininity, the sad reality is that we find Aquinas here uncritically accepting a harmful stereotype of women having weak, irrationally emotional temperaments (falsely believing this to be a natural quality of women), and then using on that “natural” stereotype to offer a complicated and problematic commentary on 1 Corinthians 6:9-10.

This is not an approach we actually need to defend, even if we still generally hold Saint Thomas in high esteem. This is simply one occasion (as with all occasions where Aquinas accepts and builds upon problematic Aristotelian views of women) that we can and should respectfully criticize him for fumbling, and set the opinion aside. Whether or not it was realistically possible for a 13th-century philosopher-theologian to have known that Aristotle’s biology of women was seriously wrong is beside the point, as a practical matter. The point is that given what we know today about how wrong Aristotle’s biology of men and women was, we cannot defend any argument that would require building upon that biological vision, and we cannot tolerate a blended framework of “effeminacy” that fails to make these critical distinctions, and quietly reinforces false and harmful beliefs regarding the nature of women.

And indeed, it must be understood that his reply to this particular objection is ultimately tangential to his main answer. Focusing too much on his response to this one objection becomes a distraction that impedes our understanding of the bigger picture. If we believe his response to this particular objection is flawed, then we can simply discard it and proceed to answer the objection in a better way. Nothing actually requires us to undertake (or resolve) a textual analysis of 1 Corinthians in order to understand that moral softness (no matter what name it goes by) is obviously a vice opposed to the virtue of perseverance. Our account of this vice is something that can stand on its own, and that we can completely understand – indeed, that we can better and more clearly understand – without falsely linking it to the nature of women.

So yes, it can be coherent to say that “the persevering man is opposed to the effeminate” [molli opponitur perseverativus], if we are extremely careful about specifying that our definition of “effeminacy” in that context is merely effeminacy-B, and nothing more. But for modern English speakers, this is deeply and needlessly confusing. It completely fails to authentically communicate the key sense of moral softness that characterizes the vice, while instantly evoking the equivocal concept of effeminacy-A that is both misleading and not actually relevant… and worse, it lends support to the confused, misogynistic and/or homophobic approaches of authors who do want to argue that men who display so-called “womanly” mannerisms are sinning, or that the vice of effeminacy is worse in men because women are naturally “more susceptible” to this vice, and proceed to invoke Aquinas to support their claims.

Finally, yes, we should also concede that human language is fundamentally conventional, and therefore – even without the influence of ancient biology – there could still be understandable reasons that the statistically-significant differential of average physical strength or weakness between the male and female sexes might tend to be translated into the parallel image of moral strength or weakness… even to the point that the etymology of virtue itself would still be derived from that stereotype of masculine strength, while “effeminacy” would still become the name for a vice characterized by the stereotype of feminine weakness. But again, no matter how understandable the origin for a term, we can (and should, and must) resist giving these sorts of stereotypes any binding or oppressive weight: because stereotypes are never a coherent basis for the formation of an authentic moral judgment. The fact that Christianity calls both men and women to be equally virtuous should be enough to signal that true femininity is never weak, that the moral virtues are universal, and that the vice of moral softness opposed to perseverance is not at all a unique sin of men, even if cultural stereotypes happen to make the contrast more intuitively visible.

Danger In The Divisions

If you have followed to this point, then perhaps it goes without saying, but: anything that confuses the critical distinction between effeminacy-A and effeminacy-B must be rejected: both because there is no authentic reason for connect them, and because blending them leads to tremendous confusion and widespread harm.

Blurring these things together – conceptually linking the ordinary dictionary definition of effeminacy to a theological vice and sin – is an obvious recipe for fueling the demon of homophobic contempt for (and self-hatred among) men who exhibit “effeminacy” in that superficial stereotypical sense. When Grant Hartley experienced feeling shame about his “perceived failures of masculinity, the way I walked and talked” (even to the point that he wanted God to “kill” those parts of himself), he was being led into sin (i.e. being scandalized, in the proper sense) by those around him who had taught him the lie that he should be ashamed for something “feminine” about himself that was not actually materially sinful. In the same way, conceptually associating weakness with effeminacy becomes an obvious recipe for fueling and cultivating misogynistic cultural attitudes, even if only unconsciously. As Chris Damian once observed, in a helpful reflection on gender:

Many want to say that women are relation-oriented, and men orient towards action. Men excel in objectivity, women in subjectivity. Men are made for strength, the story goes, and women for nurturing. But with the ballooning of these distinctions comes machismo culture, and a silent pseudo-femininity where women cannot work, or speak, or vote apart from their husbands who do these things for them. This brings insecurity for boys who value relationships or like babies or interior design, and for women with secret interests in engineering or politics. And it facilitates cultures that associate “masculinity” with violence, and “femininity” with sexual appeal and availability.

This needs to be clear, however: the mere association of certain qualities with the biological sexes is not necessarily problematic. On the contrary, there is something valuable in drawing out these gendered tensions, and interrogating the degree to which they might reflect something even only partially true; further interrogating whether a role or tendency of the biological sexes is truly given by nature will remain a critical question to unpack, if we wish to advance any sort of moral argument. But if we are simply evoking imagery or associations in a loose manner, and not advancing moral claims, then the source of an association with the masculine or feminine has relatively little importance. For nothing prevents even purely artificial gender associations or stereotypes from being reasonable and useful – for instance, in poetry or philosophy, where certain dualities (however imprecise) can help us evoke or articulate something deeper that does seem to exist, even if only imperfectly, in the dynamic roles or tendencies between the biological sexes.

The fact that a quality or tendency might not be strictly speaking natural in the deepest and most primary sense does not make it non-real or not useful to speak about. (Indeed, in a very basic but important sense: natural realities and artificial realities are both real, even if we must allow they exist in fundamentally different ways, and do not hold equal priority or stability.) Traditionally, even natural tendencies are defined as existing “always or for the most part” – such that exceptions are not impossible – and that alone should convince us to be cautious. The possibility of cultural associations not rooted in nature simply reminds us that even artificial realities can hold real power, and thus we must discern very carefully: between which roles or tendencies are more truly given by nature -vs- which are more artificially given by culture, and again between which conventional or stereotypical associations with the male or female are useful or helpful, and can be safely (however cautiously) preserved -vs- which associations are harmful or simply false, and must be resisted, reformed, or even discarded.

The problems arise not with the existence of an association with male or female, but with an excessive or rigid emphasis on those associations. In a sane world, it should be obvious that human cultures are diverse, and that individuals are multifaceted, and that personal dispositions are highly variable and rarely truly confined by stereotypes. It should be obvious that correctly discerning the line between nature and culture is sometimes extremely difficult, and that that blurring natural and cultural things is how people get confused, and that imposing rigid constraints upon gendered behavior whenever the moral law does not actually require that constraint is how you hurt people. It should be obvious that stereotypes regarding men and women can easily lead us astray if we hold them too tightly, without carefully interrogating how rooted in nature they truly are. It should not be difficult to see that abstract, stereotypical dichotomies between “masculine” and “feminine” characteristics are a double-edged sword: potentially useful and reasonable to wield, but only with great restraint.

All too often, however, we do not live in a sane world, and even reasonable visions of the “masculine” or “feminine” are easily capable of being twisted and corrupted into ugly perversions and exaggerations that cause harm. Thus we see the worldly sense of aggression and conquest as something “masculine” quietly (but logically) leading even some Christians into a stunted state not quite recognizing or knowing how absolutely essential it is to condemn the manifestly sinful machismo exhibited by popular figures such as Andrew Tate. As Ed Condon observed, in a thoughtful reflection:

Tate is, by any reasonable assessment, a vile character who boasts of sexually trafficking and physically abusing women as some kind of proof of his masculine bona fides. I’ve seen this first hand: that criticisms of Tate and what he has done, by his own proud admission, are instantly met with a chorus of mitigating rationalization for his apparent sway over a large segment of young men. His overt misogyny is appealing, and understandable, so the thinking goes, because of a broad cultural disenfranchisement of men and a vilification of “masculinity” by the feminist movement. […] Even the most guarded and qualified presenters of this point of view — and Lord knows there are plenty of them — suggest that Tate and his ilk are regrettable, on balance even bad, models for young men to pattern themselves upon, but understandable once you accept that there are no positive role models (none!) of authentic masculinity.

Andrew Tate and his sort aren’t stepping into or being produced by some absence of understanding around masculinity, they are pitching a rival version. […] Not so very long ago it was accepted without question that “goodness” was a constituent part of authentic masculinity. Its obvious absence, or the obvious presence of moral turpitude or ungentlemanly behavior, was called out as such, and those who reveled in it were seen as fundamentally lacking. A man couldn’t be “great” without being “good,” it used to be understood. Now, the two qualities are held to be contradictions. So much so that it is possible to see and hear Catholic men openly opine that constituent qualities of goodness – like self-sacrifice, humility, loving concern for the other – are weak, feminine, and fundamentally unsaleable as a pattern for manhood. Is the man who rises at 3am to feed the baby a loving father, or just a cuck? Is doing the dishes an act of modeling service, or a beta move? One wonders what these people make of St. Joseph, let alone Christ and the cross, but I’d be afraid to ask for fear of the answers.

This is a real and present problem, not a hypothetical concern. I have also personally observed this discourse playing out on social media. I have seen friends worry about rhetoric claiming that the Church alienates and emasculates men, fearing “that what I see as virtue and kindness and grace and compassion, this certain kind of man sees as ‘effeminacy’,” and I have witnessed strangers observe that the biblical fruits of the Spirit are too often labeled as “effeminate” qualities, only to have that claim instantly validated by an array of breathtaking replies, including this one:

Again, in a sane world, it should be obvious that responses like this are transparently wicked and contrary to the Gospel. It should be obvious that no true account of “Christian masculinity” can ever reasonably diverge from those qualities that Jesus Christ Himself preached and exhibited during His life on earth. And it should be obvious that we must guard against abusive claims like these, which overemphasize the sense of “masculinity” or “femininity” that might indeed be culturally associated with certain qualities or characteristics, or even basic Christian virtues.

Navigating The Nuance

In her 1931 lecture on The Separate Vocations of Man and Woman According to Nature and Grace, Edith Stein (later known as Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross) adopts a noteworthy approach when discussing gendered stereotypes:

45. Before considering men and women’s common vocation in God’s service, we would like to consider the problem of the distribution of vocations according to the natural order. Should certain positions be reserved for only men, others for only women, and perhaps a few open for both? I believe that this question also must be answered negatively. The strong individual differences existing within both sexes must be taken into account. Many women have masculine characteristics just as many men share feminine ones. Consequently, every so-called “masculine” occupation may be exercised by many women as well as many “feminine” occupations by certain men.

46. It seems right, therefore, that no legal barriers of any kind should exist. Rather, one can hope that a natural choice of vocation may be made thanks to an upbringing, education, and guidance in harmony with the individual’s nature…

Here we see Edith Stein using the terms “masculine” and “feminine” in a flexible way: one that can be shared by both men and women (at least indirectly, through various characteristics that are stereotypically associated with one sex or the other), and even applied to their stereotypical occupations (at least in an improper “so-called” sense). An approach like this is not automatically beyond all criticism, however. In her 2018 essay on Hildegard of Bingen’s Vital Contribution to the Concept of Woman, Abigail Favale offers an angle of critique on this point that merits some reflection:

The common tendency to use masculine and feminine in reference to traits and behaviors, rather than persons, signals a fractional and Cartesian impulse—fractional, because certain traits and behaviors are associated exclusively with one sex or the other (e.g., emotions are feminine and rationality is masculine), and Cartesian because gender is associated with a disembodied trait rather than an embodied person. The widespread tendency to use those terms in precisely this way signals how deeply these fractional concepts are embedded in our understanding of gender.

St. John Paul, in contrast, “never attributed femininity to a man or masculinity to a woman,” because, for him, these terms signal “two complementary ways of being conscious of the meaning of the body.” Masculinity, then, is the lived consciousness of being and acting as a male human being, and femininity is the lived consciousness of being and acting as a female human being. This adds a sense of dynamism, freedom, and individual difference to gender complementarity, as there are many possible concrete ways of being a woman, or a man, in the world.

This resonates loudly with part of a 2017 reflection offered by Chris Damian:

I was speaking with a friend who once thought of herself as a masculine woman. Her interests and desires tend towards what we often associate with masculinity. But, apparently, her husband once told her, “The things you do are feminine, not because they are feminine in themselves. But because you are feminine, and you do them.”

These words came to mind when a theology professor once defined masculinity as “charity in a man” and femininity as “charity in a woman.” This challenged me. His definition suggested that all of those traits, stereotypes, and expectations didn’t matter. Masculinity and femininity, if we follow this definition, are not things to aspire or work towards, but things which naturally manifest themselves as we live lives of creativity, love, and service.

It eschews limited or clearly delineated understandings of masculinity and femininity. A father’s nurturing of his child is masculine, because he is a man, and it is an expression of his love. He does not become feminine because he exercises tenderness. A woman’s work as an analytical engineer or a business executive does not make her masculine. Rather, her strength in this work is feminine simply because it is an exercise of her personhood.

Now, there is undeniably some merit to this approach, and even significant merit. And yet… if not held loosely, this approach also becomes deeply unsatisfying, and spirals out rather bizarrely: for if everything I do should be considered masculine, because I am male and because I do those things, then sure, by that definition, effeminacy-A could never be attributed to me. But now realize what we are saying: effeminacy-A could never be attributed to me. I could violate every cultural custom governing the social mannerisms, appearances, characteristics, or behaviors that are in fact currently associated with women, put on a dress, sculpt my nails, hair, hips, and heels to present with every stereotypically “feminine” appearance imaginable, and still claim that I must not be described as feminine or effeminate – because I am male, and femininity should never be attributed to a man; rather, everything I do is masculine.

Whatever victory or value is achieved through viewing the “masculine” or “feminine” in this narrow, technical manner, it becomes a strange and hollow victory when rigorously carried out to this logical extreme. I can achieve radical freedom from all stereotypes – indeed I can eviscerate the very concept of effeminacy-A, which now seems like something inherently problematic (fundamentally fractional and Cartesian) that should be discarded – but I will have done so at the cost of a rich cultural-linguistic heritage of useful descriptive language that evokes, captures, and articulates an array of real associations or tendencies generally exhibited by men and women (even if those things are imprecise, or perhaps fully conventional and artificial).

In other words, this solution leans toward severing our concepts of “masculinity” and “femininity” from any sort of (philosophically imprecise, but) poetic dimensions, and draining them of all (messy, but) colorful associations that human custom and culture have observed or generated, and appended to the biological sexes. It is an approach that (correctly!) senses the danger that exists in permitting gender stereotypes to exist, but then leans toward eliminating the source of the danger entirely, rather than working with them. This solves one problem (philosophical imprecision in human language), but only at the cost of exchanging it with another problem (justification for stifling descriptive or poetic language) that brings its own danger of devolving into yet another environment of exhausting, rigid language policing.

Something in the more radically person-based approach to defining “masculinity” and “femininity” may be part of a healthy solution, but it cannot reasonably be the whole solution. The benefits of clarity and intellectual precision must be held together in tension with the benefits of conventional human language, with neither nature nor custom being held too tightly – and again with neither nature nor custom being fully relinquished or abandoned. Balance is found not in refusing to acknowledge and draw upon the gender stereotypes in the culture, but simply in acknowledging distinctions and nuances, and putting in the effort to safeguard against the dangers of overaccentuating either nature or custom to the detriment of the other.

In the end, the true danger of “fractional” gender concepts arises not merely from associating certain traits or behaviors with one sex or the other, but when we go a step further and slip into thinking that certain traits or behaviors are or should be (as Abigail Favale correctly phrases it) “associated exclusively with one sex or the other”. And we can defuse that danger simply by denying any exclusivity when it is not truly required – permitting gendered associations (even purely artificial ones) to exist while being held loosely, and used in whatever ways seem reasonable. In other words: Edith Stein’s noteworthy approach was the correct approach all along.

And thus Abigail Favale’s essay also eventually point us to the ideal solution:

On the level of virtue, Hildegard connects certain virtues to women, but unlike Aristotle, there is not a corresponding devaluation of those virtues in relation to masculine virtues. And, as [Prudence Allen] points out, in Hildegard’s thought, men and women are encouraged to develop in all the virtues:

“Hildegard frequently argues that men ought to develop the feminine qualities of mercy and grace, while women ought to develop the corresponding masculine qualities of courage and strength. In this way, even though she designated particular qualities as masculine or feminine, a wholly integrated woman or man would have both aspects of their nature developed.”

It is difficult to understate just how good this solution is: embracing a healthy flexibility that is both not rigidly tied to cultural associations or stereotypes and also not entirely excluding a limited role for them. It is a solution that authorizes (indeed, encourages!) ultimately breaking away from rigid gender gatekeeping, or any phobia of presenting or behaving in a way that might happen to be culturally associated with the opposite sex. We can simultaneously ascribe a gendered emphasis (admittedly imprecise) to various qualities and virtues, and in the same breath affirm that those things nevertheless truly belong to both sexes, properly speaking.

This nuanced approach has been affirmed and echoed even at the highest levels of the Church’s teaching authority – long before Pope Francis affirmed that “masculinity and femininity are not rigid categories”. Writing as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 2004, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger penned a Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Collaboration of Men and Women, and – with the formal approval of Pope John Paul II – articulated the following:

13. Among the fundamental values linked to women’s actual lives is what has been called a “capacity for the other”… This intuition is linked to women’s physical capacity to give life. Whether lived out or remaining potential, this capacity is a reality that structures the female personality in a profound way… Although motherhood is a key element of women’s identity, this does not mean that women should be considered from the sole perspective of physical procreation. In this area, there can be serious distortions, which extol biological fecundity in purely quantitative terms and are often accompanied by dangerous disrespect for women. The existence of the Christian vocation of virginity… refutes any attempt to enclose women in mere biological destiny… Just as virginity receives from physical motherhood the insight that there is no Christian vocation except in the concrete gift of oneself to the other, so physical motherhood receives from virginity an insight into its fundamentally spiritual dimension: it is in not being content only to give physical life that the other truly comes into existence. This means that motherhood can find forms of full realization also where there is no physical procreation.

In this perspective, one understands the irreplaceable role of women in all aspects of family and social life involving human relationships and caring for others. Here what John Paul II has termed the genius of women becomes very clear…

14. It is appropriate however to recall that the feminine values mentioned here are above all human values: the human condition of man and woman created in the image of God is one and indivisible. It is only because women are more immediately attuned to these values that they are the reminder and the privileged sign of such values. But, in the final analysis, every human being, man or woman, is destined to be “for the other”. In this perspective, that which is called “femininity” is more than simply an attribute of the female sex. The word designates indeed the fundamental human capacity to live for the other and because of the other.

Cardinal Ratzinger continues to unpack this idea further, in a section on The Importance of Feminine Values in the Life of the Church, just a few paragraphs later:

16. To look at Mary and imitate her does not mean… that the Church should adopt a passivity inspired by an outdated conception of femininity. Nor does it condemn the Church to a dangerous vulnerability in a world where what count above all are domination and power. In reality, the way of Christ is neither one of domination (cf. Phil 2:6) nor of power as understood by the world (cf. Jn18:36). From the Son of God one learns that this “passivity” is in reality the way of love; it is a royal power which vanquishes all violence; it is “passion” which saves the world from sin and death and recreates humanity. In entrusting his mother to the Apostle John, Jesus on the Cross invites his Church to learn from Mary the secret of the love that is victorious.

Far from giving the Church an identity based on an historically conditioned model of femininity, the reference to Mary, with her dispositions of listening, welcoming, humility, faithfulness, praise and waiting, places the Church in continuity with the spiritual history of Israel. In Jesus and through him, these attributes become the vocation of every baptized Christian. Regardless of conditions, states of life, different vocations with or without public responsibilities, they are an essential aspect of Christian life. While these traits should be characteristic of every baptized person, women in fact live them with particular intensity and naturalness. In this way, women play a role of maximum importance in the Church’s life by recalling these dispositions to all the baptized and contributing in a unique way to showing the true face of the Church, spouse of Christ and mother of believers.

Again, it is difficult to understate just how profoundly helpful this insight is. We can speak of “femininity” in a broad sense, but still affirm that it is a fundamental human capacity. We can describe qualities as “feminine” insofar we observe most women to be associated with those things – because they are generally more immediately attuned to them, or live them out with a particular intensity and naturalness – but ultimately, the human condition is one and indivisible, and those dispositions or attributes should be characteristic of every baptized person, and thus become the vocation of every baptized Christian. Recognizing this type of “femininity” as something that properly belongs to all Christians helps us resist that ancient and recurring temptation which threatens to drag Christians into the heresy of prizing worldly power and domination (which are “naturally” characterized by the world as “masculine”), and avoid being shocked or stumbling (i.e. being scandalized, in the equivocal sense that Christ Himself scandalized to the Pharisees) when confronted by the exaltation of qualities and virtues that are “weak” in the eyes of the world (and thus characterized as “feminine”).

And indeed, this absolutely cuts both ways, as Dr. Greg Bottaro observes:

The same could be said for the masculine genius, which is a set of characteristics that are ultimately human values, attainable also by women. The integration of both sets of human values leads to human flourishing, beautifully exemplified by the father of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, described by her thus: “Hard as he was on himself, he was always affectionate towards us. His heart was exceptionally tender toward us. He lived for us alone. No mother’s heart could surpass his. Still with all that there was no weakness. All was just and well-regulated.”

We can speak of “masculinity” in a broad sense, and describe qualities as “masculine” insofar we observe most men to be associated with those things – because they are generally more immediately attuned to them, or because they seem live them out with a particular intensity and naturalness – but ultimately, we are properly describing a fundamental human capacity that all persons are called to develop, even (or especially!) if they do not find themselves more instinctively attuned to them.

This is an approach that allows us to acknowledge and embrace real differences between men and women as something loosely held – simply as associations or tendencies that are observed “for the most part” – and then immediately forestall the danger of fueling any harmful or rigid division between the sexes by pressing us to transcend those differences: encouraging both men and women to learn from one another, and calling them both equally to cultivate whichever virtues happen to not come as naturally or intuitively to them, for whatever reason.

Consequently also, if as we take Christ’s life seriously as a model – not only for Christian men, but indeed for all Christians – what we find is the world’s defective vision of “masculine” strength and “feminine” weakness shattered and remade anew, to be properly reordered along a new axis of universal virtues: gentleness and kindness are not properly feminine, nor is moral strength or perseverance properly masculine, but all of these things are simply authentically human virtues. This is the great paradox and radical, subversive scandal: that the way of Christ is not one of domination or power as understood by the world, but instead God uses what is weak in the world to shame the strong (1 Corinthians 1:27-29) – and thus anyone attempting to dissuade men from pursuing certain Christian qualities or virtues because they are “weak” or “feminine” is quite simply doing the devil’s work.

Ultimately, authentic Christian masculinity is morally identical to authentic Christian femininity, and a wholly integrated, well-rounded person will cultivate both the “masculine” and “feminine” virtues. Our worldly or cultural associations of genders with virtuous or vices are improper associations. Properly speaking, the virtues are universal, and ultimately transcend our worldly sense of which good qualities or strengths happen to be more associated with men or women, for whatever reason.

Living With The Tension

Up to this point, we have outlined the critical distinction between two different types of “effeminacy” – the quality rooted in malleable cultural stereotypes (effeminacy-A), and the actual sin opposed to the virtue of perseverance (effeminacy-B) – and we have examined the origin of how they became so closely linked in the first place. Then we grappled with the harm that is generated by confusing these concepts, and identified the roots of a deeply Catholic “both-and” style approach that can help us both defuse and transcend the (real!) dangers of cultural stereotypes surrounding “masculinity” and “femininity”, without entirely denying the useful descriptive values that those imperfect gender associations (such as effeminacy-A) can provide. Having laid all of this groundwork, there is just one closing point I wish to drive home:

No matter how defensible “effeminacy” may be as an ordinary English-language term (effeminacy-A), the moral concept located under the heading of effeminacy-B has no good claim to be called “effeminacy” at all, and therefore we should entirely cease speaking of “effeminacy” as a sin or vice, full stop. The problem is not only (indeed, it is not even primarily) the existence of a linguistic equivocation; if that were the only issue, simple encouragement to be attentive to the distinction would suffice to resolve nearly everything. The real problem is that effeminacy is just fundamentally not a good translation of the Latin mollities, and it never has been. The deep interpretive link between inconstancy and femininity was always rooted in an error, and the only way anyone can defend that translation is through accepting and building upon the (harmful) stereotype of weakness being a distinctively feminine trait.

This is not at all a criticism of the deeper moral concept of the vice itself. On the contrary, it is valuable and reasonable to have some name for the “weak” vice of moral softness (mollities) opposed to the “strong” virtue of perseverance. To be clear, it is not even inherently unreasonable to evoke a broad analogy between physical weakness and moral weakness. Neither is it necessarily a grave problem (although there may be some danger lurking) if we wish to merely evoke the stereotype of relative physical strength and weakness between the sexes. However… if ever those two components are combined – compounding the analogy to further associate moral strength with the masculine, and moral weakness with the feminine – then in that very moment we have slipped into extremely dangerous waters. For it should be obvious that any framework “naturally” linking weakness and sin to femininity is misogynistic, plain and simple.

The problem is that we have permitted our English-language readings of Aquinas to be corrupted by this equivocation that is rooted in a misogynistic-adjacent stereotype, which invites only harms and brings no meaningful benefits. Improperly calling this vice by the name of “effeminacy” simply fuels self-deception among those who (like Andrew Tate) are cultivating sexual vices under the false banner of “masculinity”. At the same time, even if we manage to avoid drifting into ugly gender stereotypes or outright misogyny, it is essentially impossible to speak about “the vice of effeminacy” at all without being immediately derailed into an exhausting (but urgent) need to parse out everything that “effeminacy” does not actually signify in the context of moral theology (where sin and virtue apply equally to both men and women, and stereotypes are never a safe basis for authentic moral judgments). The truth, then, is that there is simply no good reason to retain this terminology: it is not reasonable, it is not necessary, and it is not useful. We do not need “effeminacy-B” operating under the title “effeminacy” at all. Only “effeminacy-A” has a (still potentially thorny, but) reasonable claim to this name. The vice designated as “effeminacy-B” (mollities) should simply be renamed, to more clearly reflect and communicate what it really is at the end of the day: a moral softness or moral weakness not properly linked to femininity at all.

I conceded at the beginning, however, that this use of effeminacy is quite deeply rooted: even if we succeed in eliminating it from our own vocabulary, we will (very likely) still have to deal with it being used by others. And on this point, we can recall that: although God is perfectly capable of drawing unexpected good even out of evil, that does not mean we should cease working to eliminate evil from the world. So then also, in a similar way: even while we labor to resist the use of “effeminacy” to name a moral vice, we can still look for the silver linings, places in which unexpected goods might be drawn forth. To this end, consider Grant Hartley’s reflection:

I am sitting in the back of the chapel, listening to the homily half-heartedly… The priest turns toward expected themes of marriage and family life, and so I zone out—until I am brought back by a word that resounds sharply in my ears. “That’s effeminacy according to St. Thomas, by the way. When you blow up at your family, you are being less than a man.” Effeminacy. I am unable to stop my skin from prickling and my face from burning. I begin an imaginary argument with him in my head that keeps me from hearing fully what he says next, but from what I gather, his basic points are fine: treat your wife and children with kindness, work to control your anger, etc.

I turn to look at another man sitting in the back row, a tall, muscular middle-aged man who seems especially convicted by this homily and is weeping quietly to himself. My imaginary argument with the priest stalls, and I begin to wrestle with the fact that as painful as the homily is for me, it has had a positive spiritual effect on someone; maybe it is not my place to say anything. I think about how unexpected and difficult this charge of “effeminacy” must be for a man like him: to suddenly have the unshakeable sense that somehow the charge—at least in the way it was intended by the speaker—is true.

There is (ironically) great wisdom to found in this sort of flexible or pliable approach to human language: recognizing first and foremost the deeper reality of what the speaker intended to communicate, without letting ourselves get too derailed by philosophical imprecisions. After all, language is fundamentally a tool developed by custom, and always still fundamentally changeable by custom. Equivocations and “improper” uses of terminology are in general reasonable and acceptable: provided that we remain attentive to them, so that we can clarify our intended meaning when strict precision is needed, and also assist others in not losing sight of important distinctions.

However, when equivocal uses cease to hold any real value – when we find an equivocation (such as “effeminacy”) rooted in and reinforcing a harmful stereotype, shedding no useful light, but fueling only confusion and the harmful weaponization of that stereotype against others – then is not reasonable or acceptable. And in the end, “effeminacy-B” is not properly about femininity at all (nor, indeed, is it properly linked to homosexuality), but it is a vice truthfully just as strongly associated with stereotypical forms of male heterosexuality, as Joseph Prever once observed:

I know plenty of gay men who lisp when they talk, who sway when they walk, who are masters of personal grooming, who are stylish and histrionic. And plenty of these men have a degree of bravery, determination, perseverance, strength of mind, originality, pioneering spirit, creativity, and intelligence that any man or woman would do well to emulate. Plenty of them. Not all! Being “femme” is no guarantee of virtue, and being “masc” is no guarantee of vice. But the man who gets drunk every night in front of the TV while his wife does the dishes and raises the children – this man is more soft, more feeble, more μαλακός than the flamingest flamer. And St. Paul says that he will not inherit the kingdom of Heaven.

The husband who refuses to do “feminine” housework, but simply lounges around the house indulging in the pleasures of food and drink and smoke is mollis. The father who refuses to take a turn waking up at 3am to feed his child, because he prefers to indulge in the pleasure of sleep, is mollis. Anyone habitually assigning priority to easy bodily pleasures (food, drink, sex, comfort) and not even seriously trying to engage in the difficult work of virtue and self-improvement where it is clearly needed – anyone who rapidly gives in to the slightest temptation to abandon the pursuit of moral behavior simply because it is more pleasant to give in and allow bodily pleasures to take priority – is morally soft. In a sane world, we should be able to see this clearly, and not immediately find ourselves confused by linguistic blurring between sin and culturally feminine stereotypes. Perhaps we do not live in that sane world currently; but we should certainly be working to achieve it.

One final silver lining is perhaps the most interesting. Embedded within the wicked quality of morally pliability, there is a logical crack in the vice – something that can easily be transformed into an unexpected avenue of grace. For anyone who sincerely repents of their sin just as quickly as they fall into it – anyone who rapidly gives in to the slightest movement of grace, leaping to abandon sin just as easily as they leapt to embrace it – is also morally soft: yet in a manner that very well might not finally stand as any obstacle to their salvation. If their disordered priority of pleasure over moral goods has not yet hardened into a habitual vice that would resist repentance, then: one who “readily submits” and consents to the slightest impulse of God’s grace – although this sort of pliability is by no means an authentic virtue – may yet come to be saved (paradoxically) through the softness of their “effeminate” disposition.

“Don’t give in. Don’t you dare quit so easy; give all that you got on the sword. Don't say that you won't live forever – I know, I know.” – Snow Patrol

Thank you for this thoughtful reflection, Daniel. I feel better equipped to engage with the Aquinas bros in my life on this topic. Also nice to see a fellow Snow Patrol fan out in the wild. I saw them back in 2012 with Ed Sheeran opening (!?), in case I needed another reminder than I could not have predicted a decade ago how our world would look today.

Sooooo...you are saying that men and women are the same. Got it. 😆

Another excellent, thoughtful and well-written and researched article, Daniel.

I think a lot of what passes for "masculinity" today is insecure learned behavior from school days. I also think the really natural manly men (e.g. John Farrier) spend much time thinking about 'the problem with all the effeminate men these days'.

That's a great callout on the Aristotle/Thomas point. I give Aristotle a bit more *grace*, given that, as men are generally more interested in abstract ideas, solving all problems with logic, settling relationship dynamics by dominance, etc., he and his bros thinking naturally "hmm, these are the things we think are most important, and men generally pursue them more/are better at them.

This is another point in the case for Thomas to be praised as a great systematizer, rather then a great philosopher. I think the fullness of humanity, as seen in Christianity gives him much less excuse for a crude claim like 'women are sub-men', particularly since he is willing to critize Aristotle on other points and say that the Philosopher was missing a part of the truth...