This is another deeply complex topic – and not one that I intend to explore often in the future. Regarding the moral and geopolitical dynamics of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, several interviews are linked at the end, with experts in the subject matter whose opinions are more well-formed than mine likely ever will be. My focus here will be much more theological in nature, zeroing in on a specific insight extracted from one of the many interviews on this topic that I have listened to in recent months.

Part I: Worldly Splendor

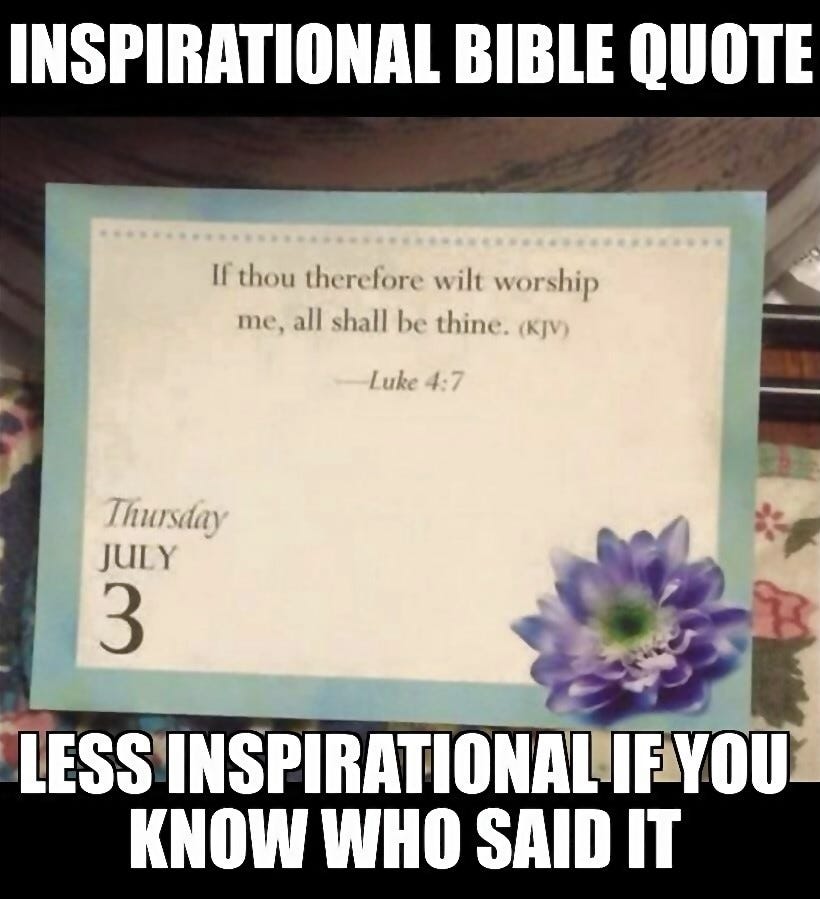

Perceiving then that they were about to come and take him by force to make him king, Jesus withdrew again to the hills by himself. – John 6:13-15, RSVCE

Again, the devil took [Jesus] to a very high mountain, and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and the glory of them; and he said to him, “All these I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.” – Matthew 4:8-9, RSVCE

In his book Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, Pope Benedict XVI (born Joseph Ratzinger) offers a reflection on the difficult relationship between the Christian faith and worldly power. While discussing this temptation that Satan offered to Jesus in the desert, he observes that:

“The Kingdom of Christ is different from the kingdoms of the earth, and their splendor, which Satan parades before him. This splendor [is] an illusory appearance that disintegrates. This is not the sort of splendor that belongs to the Kingdom of Christ. His Kingdom grows through the humility of the proclamation in those who agree to become his disciples, who are baptized in the name of the triune God, and who keep his commandments (cf. Mt 28:19f.).” [pg. 39]

“The Lord [declares] that the concept of the Messiah has to be understood in terms of the entirety of the message of the Prophets – it means not worldly power, but the Cross, and the radically different community that comes into being through the Cross. …The Christian empire or the secular power of the papacy is no longer a temptation today, but the interpretation of Christianity as a recipe for progress and the proclamation of universal prosperity as the real goal of all religions, including Christianity – this is the modern form of the same temptation. …“O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken!” (Lk 24:25). This is what the Lord said to his disciples on the road to Emmaus and he has to say the same to us repeatedly throughout the centuries, because we too are constantly presuming that in order to make good on his claim to be the Messiah, he ought to have ushered in the golden age.” [pg. 42-43]

And indeed, there is a unique danger inherent to the desire for worldly power:

“The Christian empire attempted at an early stage to use the faith in order to cement political unity. The Kingdom of Christ was now expected to take the form of a political kingdom and its splendor. The powerlessness of faith, the earthly powerlessness of Jesus Christ, was to be given the helping hand of political and military might. This temptation to use power to secure the faith has arisen again and again in varied forms throughout the centuries, and again and again faith has risked being suffocated in the embrace of power. The struggle for the freedom of the Church, the struggle to avoid identifying Jesus’ Kingdom with any political structure, is one that has to be fought century after century. For the fusion of faith and political power always comes at a price: faith becomes the servant of power and must bend to its criteria.” [pg. 39-40]

Part II: What Happened To Us?

Earlier this year on Tangle (which you should be subscribed to) Isaac Saul published yet another in-depth interview on the topic of Israel and Palestine. And at the time – somewhat exhausted by the number of interviews on the topic I had already consumed – I was skeptical that I would find it valuable. But then, roughly one-third of the way into the interview, the speaker launched into a long but fascinating background explanation, shedding a helpful theological light on the origin of Hamas.

This past week, in his criticism of Benjamin Netanyahu’s addresses Congress on the war in Gaza, Isaac referred back to this interview, summarizing it in this way:

Even if we can expect some level of dehumanization of enemies in war, reducing Hamas to simply "evil" and the Palestinian movement to "barbarism" makes it impossible to grasp this conflict with any depth. I interviewed Israeli analyst Haviv Rettig Gur, who made the strong point that Hamas is a group operating within a centuries-old context of complex political, religious, and philosophical thought. Understanding what motivates Hamas (and their supporters) is critical to achieving any lasting peace, but the reductive terms Netanyahu employs will only obscure that understanding.

You can (and probably should) listen to the whole interview – available on YouTube or Apple Podcasts or Spotify – but here below I will provide a transcript of the most relevant middle third of this interview, lightly edited for readability:

There is a camp that I think is sensitive to international discourse, and wants Westerners who want to like Hamas, because Hamas is all the Palestinians are giving them. And they don't want to not like Palestinian politics, because that lets the Israelis off the hook. That kind of thinking drives you to look for any possible way to absolve Hamas of being Hamas, of its most fundamental ideology and vision of history and understanding of how you get to a better future, which is by the destruction of Israel. […] But, you know, I want to say two things in favor of that sort of Western opinion you described, where people say Hamas has the potential to be or is developing into a more sophisticated [organization].

First of all… you phrased it in this real liberal gaze. What does that mean, that if they become more palatable to me, then they're more sophisticated? It's not just you, by the way, everybody in the State Department talks this way. Anthony Blinken tells the New York Times on the Iranian regime: it's time for the Iranian regime to decide whether it wants to be a responsible member of the family of nations… as if these people don't have a deep vision of history, but in fact they're 11-year-old boys jumping in a puddle, and we just wish they would stop jumping in a puddle.

To be clear, I am trying to parrot the kind of Western framework to elicit this response from you, because I think that's important. Independently, that's not how I would speak about it, but that is the framing that I hear over and over again – that they're becoming more sophisticated, they're becoming an organization that might be able to be a future partner, etc.

Right, so two points. One… at their cruelest and most brutal, they're extremely deep, thoughtful, sophisticated, careful planners, intelligent people, who live as vividly as we live, and understand the world with the same depth that we understand the world. And I apologize but I do think that when [most progressives] look at the Middle East, and they see a group like Hamas, their reaction – born out of ignorance, not malice – is a prejudiced one, not a serious humanizing one.

Hamas has a story, and it's a story it tells Palestinians, and Palestinians like the story. Even when they hate Hamas, they like the story. And if we understand the story... do we have time?

Sure, please.

Okay, I want to make Hamas look sophisticated without turning into something palatable to Western liberals. It's always sophisticated… and it might moderate, I don't know, but it's still clever even if it doesn't. And people in the West really have a hard time imagining – people say “What would lead you to massacre children?” Well, I must be really hurting is really the only answer the Westerners can imagine. But that's a failure of the Western imagination, that's not an actual diagnostic analysis of Hamas.

Hamas is born out of essentially a Muslim debate that's been going on for about 150 years within Islam. Serious, rich, intelligent debate that is much more courageous than anything happening in Western academia today. And it's a debate over this question of why Islam is weak. The most important theologians and thinkers of Islam have looked at Islam for the last century and a half – a lot of this was especially sparked by the weakness of the Ottoman Empire in its last decades, and by the growing power of Western empires coming in and carving up the Middle East – and so it becomes something you can't avoid, and Muslim thinkers start to ask serious questions, and publish new journals, and really a rich discourse – in the Arab Sunni world especially, that's at least the part that I know well – they have this rich discourse in which they ask: What happened to us?

Islam used to be the commercial power of the world, the geopolitical power of the world, it used to produce empires that would in 100 years conquer all the way to the middle of France and halfway to Afghanistan in the other direction. In Islam's first 100 years, right? And now we are weak, we are backward. Islam was the forefront of science, in the 16th century the largest astronomical observatory in the world was in Istanbul, or Constantinople then. Under Islam, it was not in Europe under Christianity. What happened to us?

And how you answer that question produced the Muslim world of today. In other words, in its sort of most fundamental sense, Arab nationalism is an answer to the question: What happened to us? And Al-Qaeda, at its fundamental intellectual core, is an answer to the question: What happened to us? And therefore also [is] how we get back to a place of power and agency in history.

For Muslims, this is a key point. For those theologians 150 years ago... by the way, there are a billion and a half Muslims, and there's probably more diversity in Islam than there is in the West, and so apologies for talking about “Islam”… it's too big a word to even use coherently as a word, but nevertheless, we have to talk about it, so I'm just going to talk about it. For those Muslim thinkers a century and a half ago, this question of: What happened to us? Why are we weak? Why are we backward? Why are we not what we were 400 years earlier? It's not a political question, and it's not a policy question. It's a theological question. And the reason it's a theological question is that early Islam – as it conquered, as it exploded onto the world scene, and crossed continents in a few decades – it was as surprised by its conquests as the people it conquered were surprised. And it concluded, it developed an internal discourse within Islam that saw that astonishing success as evidence of the truth of the revelation to Muhammad, as evidence of divine grace.

It's a very simple idea. It's an idea contained in Judaism and Christianity. The idea basically is there's a God, it's a God of justice, God oversees history, therefore history has an arc, a purpose, an end goal. That end goal and arc and purpose is toward justice. And so, there is this trajectory to history. That's an idea shared by Jews, Muslims, and Christians. Muslims make a leap that Jews never made, which is: therefore if I am powerful in history, I am in sync with that divine plan, right, I'm synchronized with that divine trajectory for history. Jews never made [that leap] because they never were powerful in history. [But] if I am conquering a continent in 10 years, or 40 years, that must mean that I'm true, and I'm close to God, and God's favor is with me.

And therefore, if you're living in Cairo in 1890, and you're a theologian at Al-Azhar, and you're watching the British take Cairo from the Ottomans without even asking politely, you're asking yourself: What happened to us? You're not just asking yourself: How geopolitically did Islam grow weaker than Europe? What you're actually asking yourself is: How did we lose God's favor? How did we lose God's grace? And you see the beginnings of the development of ideas that are really ideas of Islamic renewal. What we today call Islamism, or Islamic radicalism, or extremism, or terror groups, are all kinds of versions of this idea of answers to this question: How do we restore the old piety of Islam that ensured geopolitical power, because it ensured closeness to God?

And so, that's what Al-Qaeda is. That's what the Muslim Brotherhood are. That's what Hamas is, which is essentially a chapter of the Muslim Brotherhood established in Gaza in 1987. Hamas doesn't fly Palestinian flags. Hamas doesn't sell Palestinians on the nationalist story. Hamas doesn't like nationalism. It thinks nationalism is a European construct imposed on the Muslims to divide them and weaken them. Hamas believes in this Muslim renewalist vision. And this is really important because it gets to the heart of why Israel is so important to the terror organizations of the world, [and] to the Iranian regime. The Iranian regime has spent untold billions on the destruction of Israel. Why? Why does it care?

When I went on a campus tour in the U.S. and I met a lot of these students and saw a couple of encampments, the tragedy for me with these kids isn't that maybe some of them are a little bigoted and ignorant, which is the complaint. The real tragedy for me was that they're uncurious! They're not doing the thing you're supposed to do at university, right? Why does Iran actually want to destroy Israel? It's not obvious. Israel is far away. It's certainly not doing it for Palestinian rights. You're not going to convince me the Ayatollahs care about rights. What's it about? And the answer is really interesting and important.

If you're a Muslim theologian, I send people to a guy named Rashid Rida. He's one of the more important thinkers in 19th century Egypt, who established Salafi Islam in the modern age. And he's also a teacher of some important Palestinian leaders [who shaped the Palestinian National Movement] in the '30s into what it is today. And these are people who learned from Rashid Rida. Rashid Rida is a man sitting in Cairo in the 1890s, and he's writing this sort of Salafist argument about returning to a piety that will restore us as a strong power in history.

He writes a letter – just an astonishing letter that I'm going to paraphrase, but quite accurately, I hope – in a journal that he publishes in 1898 called Al-Manar, which is one of the most influential journals in the Sunni Arab world at the time. And in this letter, he addresses it to the Palestinian Arabs in 1898.

1898 is a very interesting year because it's the year after the first Zionist Congress, whose minutes Rashid Rida followed very carefully. He's listening to the Zionists, and he turns to the Palestinian Arabs. By the way he's pro-Zionist at the very beginning because he thinks the Zionists, the Jews and the Muslims are going to team up to kick out the Christian empires. He then turns against Zionism, and he turns against Zionism on the question of Islamic weakness.

He writes this letter to the Palestinian Arabs in 1898 where he says to them, he opens with, “You complacent nothings.” It's not a very polite letter. He's actually enraged. “You are going to allow the weakest of all nations, the paupers of the earth, those expelled from every land in civilization, to push you back and become masters in your land.” His problem with Palestinian Arab reaction, or failure to react properly, as he sees it, to the very, very early Zionist immigration – we're talking about a thousand people a year, two thousand people a year, in those years – his problem with them is that he begins to understand that what the Zionists want to do is establish a nation state, and not a Muslim state. And so, it's not about Palestinian nationalism, he's never heard of Palestinian nationalism. It's not about democratic rights, again, he's unconcerned by democracy, that's not what animates him. He's worried about the fact that the Jews, who will establish a Jewish territory in Muslim lands, are so weak.

In other words, he's a Muslim theologian, living under British rule – which is inconvenient, it's unpleasant, it's theologically problematic – but the British Empire at the time is maybe the most powerful empire in the history of the world, so it's not that problematic. Islam should be on top, but it's not like catastrophic if it's under the most powerful non-Islamic empire. But if the Jews of 1898 can push Islam back… Who are the Jews of 1898? Who are your great-great-grandparents? They’re people fleeing, with nothing but the shirt on their back, 1300 pogroms over 40 years in Eastern Europe. They’re people who land in New York Harbor without a dollar… they’re desperate paupers fleeing mass oppression and pogroms across a dozen countries. If that weakest of all peoples can push Islam back, then the disaster – the theological disaster – of Islamic weakness becomes intolerable. It just becomes too great.

Why does Iran want to destroy Israel? Why does Hamas think that the destruction of the Jews is so great a goal? The destruction of the Jews – not two states, not liberation for Palestinian nationalism – [that’s] just not what Hamas wants and how it talks. I tell people just go to their mosque and listen to every sermon every week in every Hamas mosque… Not all progressives support Hamas, I [don’t] mean to imply that, but of that far-left edge that does talk positively about Hamas, Hamas disagrees with you – not I disagree with you, Hamas disagrees with you. But what does Hamas actually say?

What Hamas actually says is that Islam is now weak, and Islam is weak because it is impious, and it is far from God. And if it returns into God's grace, it will be strong. What's the best signal of the beginning of an Islamic return to piety and therefore God's grace? A return to strength. What's the weakest thing that ever pushed Islam back? The Jews of Israel.

So the first step, the first signal of Islam's return… Hamas is a Islamic return renewalist movement. By the way, the Iranian regime thinks the same way, in Shia terms, and there's a whole lot of diversity here, but nevertheless: Iran needs to destroy Israel desperately, and will spend anything it needs to do it. Because it's trying to restore Islam. That's the meaning of the revolution. And that has to begin with the weakest thing that ever pushed Islam back. That's the first step of Islam returning into history.

My key point here is, when Westerners look at Hamas and say well, they're not moderate, they're extremists, but they could moderate over time… they think that, like, everything is emotional outburst, they think, well, you know, brown people just have trouble controlling their emotions, so their entire political universe is one emotional outburst after another, and if we treat them nicely, they'll be nice people.

Palestinians have rich, deep, old thoughts and stories about the visions of history. There's bookshelves, there are libraries that drive the ideas that drive Palestinian politics – including what's dysfunctional about Palestinian politics. I don't know how Western liberals let themselves get away with cartoonizing. [And] they do it to me, and it makes me angry at them, because it's racism – it's a kind of bigotry, that sort of shrinking of other people into your moral cartoon, and thinking you've encompassed them. But they're even doing it to Palestinians! And their whole point is that they don't want to do it to Palestinians. So, Hamas did not moderate. It didn't grow more sophisticated, because it's always been very sophisticated.

And, I'm going to stop talking. I do have one more thing to say, which is nevertheless… there could be a moderate version of Hamas. And the reason there could be a moderate version of Hamas – but you really have to know something about Arab-Palestinian Islam, about how Islam works in Palestinian society to actually see it – and this is interesting, and progressives generally miss it.

There's a political party inside Israel, an Israeli-Arab political party called Ra'am. The Ra'am political party is Islamist. It is born in the Muslim Brotherhood tradition that founded Hamas. It is a sister political movement to Hamas. Also, it's pacifist. And it actually, within its religious institutions, has given a Sharia ruling that the state of Israel is a Jewish state. “For some reason, right now, God wants the Jews here. We don't know why, but that's okay.” The party actually has a long history of connection with Hamas, and that's really important to understand. Its founder, Sheikh Nimr Darwish, was actually engaged in terrorism in the 1980s. He was imprisoned by Israel… and then he turns pacifist. And he founds the Islamic movement of Israel, which is essentially the religious version of what Hamas is in Palestinian society. And when he turns pacifist, the Islamic movement splits in two. To this day, there's a northern Islamic movement, which holds to the violent strategy of Hamas, and most of its illegal in Israel today… and there's a southern movement, whose main constituency is the Bedouin of the south, of the Negev, and is ideologically Salafist renewalist, but also pacifist.

Mansour Abbas, the leader of the party, is also one of the disciples of Nimr Darwish, who passed away a few years ago – and he has given interviews on Israeli television in Hebrew, in which he says things like: “The state of Israel is a Jewish state, and it's going to be a Jewish state, and that's okay.” And the reason he's okay with it, even though he's an Islamic renewalist Salafist, is because… and just the way people around him talk, is basically to say: “We're actual believers. Hamas are not believers. I know that in the end of history, all the Jews, they're all going to be Muslims. And all the Christians, they're all going to be Muslims, too. God has an arc, and a vision, and a purpose to history, and therefore, because I am an actual believer, I don't have to massacre children to make it happen. And so my problem with Hamas is that, the very fact that they're willing to turn to this kind of anti-colonial brutality – modeled on anti-colonial wars like Algeria, the Algerian independence war against the French – proves that they don't actually believe. They're not actually people of faith.”

So there are versions of the same ideological world of Hamas, that are exactly what, you know, I think progressives wish the Palestinian National Movement would be, because then they wouldn't have to actually fight over whether or not terrorism's okay, right? Now I'm really going to stop talking.

Part III: Christian Nationalism

As Christianity continues to lose its former political power in the world, modern Christians – especially those who adhere (consciously or unconsciously) to some form of so-called “prosperity theology” (or the heretical “prosperity Gospel” doctrine) – face a very similar “theological crisis”. For the belief that “if I have faith in God, God will give me security and prosperity” is nothing other than a new version of that same theological leap outlined above: “if I am powerful in history, I am in sync with the divine plan” inverted to “when I am in sync with the divine plan, I will be powerful”.

And thus the same corresponding temptation arises: What happened to us? The United States may have material strength, but it is morally corrupt, no longer the majority Christian nation it once was in the 1950s. Why are we Christians weak? Why are we not what we were 70 years ago? Perhaps Christianity in America is now weak because it is impious, and it is far from God. And if it returns into piety, it will secure God’s grace, it will become great again. What’s the best signal of a return to Christian piety, and therefore God’s grace? A return to political strength. The roots of theological radicalism and political extremism thus find fertile soil in the implicit question: How do we restore the old piety of our nation that made the United States great, because it ensured closeness to God? Christian nationalism thus appears as a tempting answer to the deeper question posed by the crisis of Christian political weakness: obtain worldly political power, and wield it to forcibly re-write social mores from the top-down.

Nor are well-meaning, historically-minded Catholics immune from this temptation. We have lost the Holy Roman Empire, and the Papal States. Why are we not what we were 800 years ago? What happened to us? Indeed the temptation for American Catholics is effectively doubled and compounded, particularly when there is a heightened intellectual interest in magisterial teaching on integralism.1 For perhaps living in a non-Catholic empire is inconvenient, and unpleasant, and theologically problematic… but the American empire is maybe the most powerful empire in the history of the world, so it’s not that problematic. Catholicism should be on top, but it’s not like catastrophic if it’s under the most powerful non-Catholic empire. At the same time, the manifest cultural collapse of Christian piety has rendered the Catholic Church weak. And what’s the fastest way to make the Church strong again? Support for Christian nationalism, and thereby a return to political strength, through a useful alliance with our Christian neighbors who appear to share so many of our values.

And the temptation draws more fuel from looking outside of our borders. Perhaps everyone (or almost everyone) has turned on the autocrat Vladimir Putin, due to his warmongering; but if not for that war, many would surely remain tempted to praise his authoritarian crackdown on various moral evils as a form of “great control over his country”. Even now, many conservatives are tempted to look to Viktor Orbán and his explicit efforts to reinforce “Christian values” in Hungary (through abandoning liberal democracy in favor of an “illiberal state”, quite explicitly in imitation of Russia) as a praiseworthy example of a Christian leader that could be imitated in America.

Look, I don’t have all the answers here.

I have principles, and serious concerns, not a clean thesis statement.

But I know that how we respond to the temptation of power and worldly splendor matters. I know that how we use (or acquire) our political power matters. And I agree with Pope Benedict’s concern regarding the fusion of faith and political power.

I know that violence is not how we spread the Gospel (see Matthew 26:52). I know that weakness in the eyes of the world is no true cause for any theological crisis (see 1 Corinthians 1:27). And I know that social minorities have always held a privileged place in God’s plan for the salvation of the world.2

I know that worldly splendor is a quicker, easier, and more seductive pathway to many abilities political powers some consider to be unnatural authoritarian. Thus I understand that whenever we do hold (or seek to hold) political power, the manner in which use that power matters, as well as the manner in which we aim to structure (or restructure) our society with that power – perhaps above all, regarding the treatment of social and political minorities who disagree with those in power.

And of course, the modern theological-political crisis facing American Christians is not identical to the historical theological-political crisis that gave rise to Islamic radicalism or extremism and terror groups. One might even hope that Christians are, by virtue of their most fundamental doctrines, at least relatively well-immunized against the rise of any long-lasting heretical movements that would embrace physical violence as a means to power. But there is no denying that the temptation is present, and the deep theological similarities in the roots of that temptation merit further reflection. How we respond to the temptation of worldly splendor matters – but the first step is seeing the temptation for what it is, understanding the depth of its roots, and apprehending the true gravity of the seemingly small prices it asks us to pay.

Addendum: October 2024

I am pleased to see that Tangle has now published a reader essay by Joshua Majeski articulating an Evangelical perspective on this same point of resonance that had struck me from a Catholic perspective. (He even used a similarly alliterative title!)

For further exploration of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict:

If nothing else, I strongly recommend devoting the time to listen to Daniel Bannoura, a Palestinian Christian and deeply thoughtful Palestinian advocate, particularly his February 11th 2024 interview on the Tangle podcast (on Apple Podcasts, and Spotify). Seriously, if you listen to only one interview, pick this one. It’s worth your time.

Other deep-dive interviews I’ve listened to in recent months, and found clarifying:

Israel and Palestine Origins with Dr. Benny Morris (on YouTube)

Debating the Israel-Palestine Conflict with Yousef Munayyer (on YouTube)

A Firey Debate on Israel & Palestine with Isaac Saul, Dan Cohen, and Hussein Mansour (via Tangle News: A brief introduction and links to watch.)

A Palestinian Christian's Perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian War: Daniel Bannoura (on YouTube)

For Catholic intellectual defenses of integralism, see for example Thomas Pink (also interviewed by The Pillar here) and John Brungardt. But at the same time, see also James Heaney for an equally Catholic intellectual defense of liberalism. And indeed, at least as matter of academic theory, it may even be possible to harmonize these things. But that is…

If the entire history of the Jewish faith does not already make this abundantly clear to Christian readers, consider that – even in a thoroughly Christian framework that absolutely considers the New Testament to be the fulfillment of God’s covenant with Israel – we are nevertheless forced to recognize that the Jewish faith still persists, in God’s providence, for some reason we do not understand. And maybe the best thing Christians can say is simply: “For some reason, right now, God wants the Jews here. We don’t know why, but that’s okay.” Or perhaps Christians can recognize that God always desires His chosen people to serve as a stumbling block to those in power, even more than He desires them to hold power. Maybe we still have a lot more to learn from the blessedly stubborn example of a divinely-chosen religious minority that has never held immense worldly power. Maybe God wants our Jewish siblings to actively preserve the memory of a faith that many Christians would be tempted to forget, after having tasted power. Maybe Jesus always loves social minorities, and always wants those who hold power to ensure that they are protected and preserved, even in the most robust Christian or integralist Catholic society, is kind of what I’m getting at.