Fragments: Against Despair

"When you're lost in the universe, lost in the universe, don't lose faith. My mother said, ‘Your whole life's in the hand of God.’ Nothing has changed, He is the same." – Jon Bellion (Hand Of God)

As we approach (or, well, as most of us approach)1 the winter solstice – the darkest day of the year – there can be a common tendency to experience greater temptation toward despair in the midst of the long darkness. Christians sometimes push back against this tendency with a more intellectual-theological emphasis: focusing on the impending celebration of Christmas – the Incarnation of the Light of the world – and the subsequent gradual-but-inevitable increase of natural daylight in our lives, which is indeed a wonderful (and convenient)2 bit of theological symbolism.

Outside of the Christmas season, Christians also sometimes push back against this tendency with a more visceral-poetic emphasis: creating alt-metal rock songs that shout “You'll never be alone; when darkness comes, I'll light the night with stars”, or finding unexpected spiritual threads in non-religious EDM songs with refrains like “I will find you in the darkness” that (accidentally, yet easily) resonate with an optimistic anagogical and eschatological interpretation in line with the voice of a Creator who “chases me down, fights 'til I'm found, leaves the ninety-nine”.

Anyway, I think there is value in both the intellectual-theological and the visceral-poetic approaches, so I’m going to try leaning on a bit of both.

Fragment 1: Hope Amidst Temptation

Excerpts from “Chastity: Reconciliation of the Senses” by Bishop Erik Varden:

Abba Antony speaks for mainstream tradition when he says that the body’s impulses as such are natural and morally neutral. Yet a twisted, passionate urge can cause these impulses to diverge from nature. This urge appears in two forms.

The first is purely physical. It comes about when we pamper our bodies voluptuously. This is why the pursuit of chastity is inseparable from fasting, which we should understand not merely as disciplined eating but as a psychobiological, therapeutic practice of liberation from self-centeredness. The second form of the passionate urge is spiritual, born of the devil’s jealousy. The father of lies does not want us to be sanctified in truth. He confounds us where we are most vulnerable.

A sign of a given temptation’s diabolical origin is its tendency to induce hopelessness. A monk who falls prey to it thinks that he is abandoned by God; that for him there can be no pardon. This is the greatest temptation. The Apophthegmata [Sayings of the Desert Fathers] praise monks who, in battle against impurity, refuse to abandon hope of God’s grace (V.47). Even the darkest thoughts are powerless if we do not grant them entry to our heart… Trouble begins the moment we close our eyes and entrust ourselves to the tempter’s soft voice, which draws us into the realm of chaos from which it issues. [p. 142]

…the superior ascesis consists in courtesy, a high form of self-transcendence. We find this principle more dramatically illustrated in the story of a young monk tormented by impure thoughts. When he went to an abba to open his heart, the old man, in spite of his grey hair and beard, turned out to be ἄπειρος [Greek: apeiros], ‘without experience’: he violently scolded the brother and told him that a man who entertains such thoughts is unworthy of the monk’s habit. The young disciple was saddened, lost heart and decided to abandon monastic life. Thank God, on his way back into the world, he ran into Abba Apollos.

Apollos was a perceptive man. He had eyes to see. He noticed at once the brother’s burden of sadness, and asked, ‘But child, why are you so downcast?’ The young monk told his story. Apollos consoled him: ‘Child, this is nothing to be astonished about. Don’t give up hope! I myself, ancient as I am, am often plagued terribly by thoughts! Don’t lose courage on account of a fever which no human zeal, but only God’s mercy can heal. Give me a day or so, then you can return to your cell.’

The young man settled down, heartened, while Apollos took his staff and went to pay a visit to his old colleague, the one who had been harsh. Taking position outside this man’s cell, Apollos prayed: ‘Lord, you let temptations come to those who may benefit from them. Let [my young] brother’s battle be transferred onto this old man so that he ... may experience what a long life has not taught him, so to show mercy to those who do combat.’

Apollos’s prayer was heard. Forthwith the old man came running out of his door, shouting ‘like a drunkard’, unable to endure the temptation, running for the world. Apollos stopped him and explained what was going on. With high sarcasm he said, ‘Probably the devil thought you unworthy of temptation, and that is why you were cruel to the brother who was having a hard time’ (V.4).

This story teaches us a lot: that the weakness of the flesh is a universal experience; that sexual temptations are composite; that temptation can serve a useful purpose if it leads us into humility; that acquaintance with our own weakness teaches us compassion with others; and that we, when we see another human being in truth – weak but with capacity for and will towards the good – see him or her the way God sees them, that is, with infinite mercy. [p. 144-145]

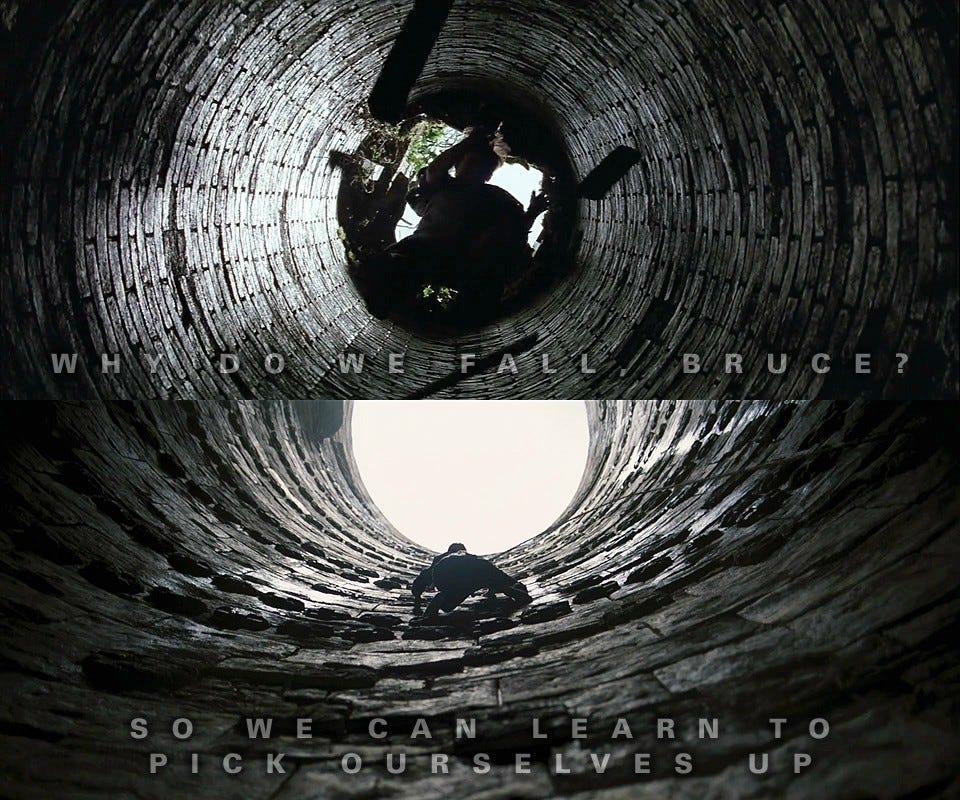

Fragment 2: Why Do We Fall?

CCC 412: But why did God not prevent the first man from sinning? St. Leo the Great responds, “Christ’s inexpressible grace gave us blessings better than those the demon’s envy had taken away.” And St. Thomas Aquinas wrote, “There is nothing to prevent human nature’s being raised up to something greater, even after sin; God permits evil in order to draw forth some greater good. Thus St. Paul says [Romans 5:20], ‘Where sin increased, grace abounded all the more’; and the Exultet sings, ‘O happy fault... which gained for us so great a Redeemer!’”

[citing Aquinas: Summa Theologiae III, Q.1, A.3, Reply to Objection 3]

From “The Handbook on Faith, Hope and Love” by Saint Augustine (Chapter 11):

For the Almighty God, [who] has supreme power over all things, being Himself supremely good, would never permit the existence of anything evil among His works, if He were not so omnipotent and good that He can bring good even out of evil.

From “The Ladder of Divine Ascent” by St. John Climacus (Step 15, n. 32):

I ask you to consider this question: who is greater, he who dies and rises again or he who does not die at all? Those who extol the latter are deceived, for Christ both died and rose. But he who extols the former urges that for the dying, or rather the falling, there is no cause whatever for despair.

Fragment 3: Non-Sacramental Reconciliation

So this section is less of a fragment, and more of a deep-dive – but bear with me, because it is worth delving into the theological-canonical weeds here to really get a handle on the much simpler point that ultimately stands as a “fragment”.

When the Catechism of the Catholic Church discusses repentance (also called contrition), it makes a fundamental distinction between perfect and imperfect repentance: “If repentance arises from love of charity for God, it is called ‘perfect’ contrition; if it is founded on other motives, it is called ‘imperfect’.” (CCC 1492)

Imperfect contrition is “born of the consideration of sin’s ugliness or the fear of eternal damnation and the other penalties threatening the sinner” – it is also called contrition of fear, or even simply attrition. This stirring of conscience is “a gift of God, a prompting of the Holy Spirit” which “can initiate an interior process which, under the prompting of grace, will be brought to completion by sacramental absolution. By itself however, imperfect contrition cannot obtain the forgiveness of grave sins, but it disposes one to obtain forgiveness in the sacrament of Penance.” (CCC 1453)

Perfect contrition, on the other hand, “arises from a love by which God is loved above all else” – it is also called contrition of charity. This form of contrition “remits venial sins; it also obtains forgiveness of mortal sins if it includes the firm resolution to have recourse to sacramental confession as soon as possible.” (CCC 1452) This doctrine – affirming the existence of a non-sacramental manner in which not only venial sins but even mortal sins might be forgiven apart from sacramental confession – might be surprising to Catholics who were raised to absorb a more rigid idea about the extreme urgency of seeking sacramental absolution; yet the source of this teaching traces back directly to the Council of Trent, Session 14, Chapter IV:

The council teaches furthermore, that though it happens sometimes that this contrition is perfect through charity and reconciles man to God before this sacrament [of confession] is actually received, this reconciliation, nevertheless, is not to be ascribed to the contrition itself without a desire of the sacrament, which desire is included in it.

Now, it is important to not misunderstand this: the existence of a non-sacramental means of having our sins forgiven is by no means any sort of license of avoid seeking out sacramental confession in a reasonably urgent manner, when necessary. One of the most important reasons that the sacrament of confession exists in the first place is because it gives us certainty about the forgiveness of our sins, through a personal encounter in which we are able to hear the words of absolution, and through knowing that the sacrament bestows complete absolution of all sins (including mortal sins), even if we only have imperfect contrition for those sins. It is important to pursue and utilize the advantage of the sacrament of confession so that we do not slip into false certainty or self-delusion about the existence (or nature) of our contrition.

But knowing that God is not limited by His sacraments can become a tremendous weapon against any sort of anxiety that would fuel a spiritually and/or psychologically unhealthy relationship with the sacrament of confession. And indeed, our confidence that God does bestow His grace of justification and forgiveness upon those who are sincerely desire to receive them, even apart from His sacraments, is a truth deeply related to the Church’s doctrine on the efficacy of baptism of desire, which similarly “brings about the fruits of Baptism without being a sacrament” (CCC 1258-1260).

This reality also helps explain why the law of the Church appears almost shockingly non-urgent when it obliges the faithful only “to confess their grave sins at least once a year” (canon 989) and why there is a fascinating (and otherwise inexplicable) “unless” clause attached to the Church’s law governing the reception of communion:

Canon 916: Anyone who is conscious of grave sin may not celebrate Mass or receive the Body of the Lord without previously having been to sacramental confession, unless there is a grave reason and there is no opportunity to confess; in this case the person is to remember the obligation to make an act of perfect contrition, which includes the resolve to go to confession as soon as possible.

CCC 1457: Anyone who is aware of having committed a mortal sin must not receive Holy Communion, even if he experiences deep contrition, without having first received sacramental absolution, unless he has a grave reason for receiving Communion and there is no possibility of going to confession.

The only reason this “exception” can coherently exist at all is because a sincere act of contrition motivated by charity reconciles man to God, and absolves even grave sins in an extraordinary manner apart from the sacrament, thereby enabling (for a grave reason) the reception of communion without any sacrilege. Again, see also:

Canon 960: Individual and integral confession and absolution constitute the sole ordinary means by which a member of the faithful who is conscious of grave sin is reconciled with God and with the Church. Physical or moral impossibility alone excuses from such confession, in which case reconciliation may be attained by other means also.

And here, we can begin to apprehend one final (but interesting and important) point: even when we can believe that God has already forgiven our sins in a extraordinary non-sacramental manner – indeed, even when our sins have been certainly validly forgiven in an extraordinary sacramental manner through general absolution (see canons 962-963) – this reality that our sins have been truly forgiven (via extraordinary means) coexists with the law of the Church nevertheless still obliging us to obtain ordinary sacramental forgiveness when it does become available to us.

Canon 988 §1: The faithful are bound to confess, in kind and in number, all grave sins committed after baptism, of which after careful examination of conscience they are aware, which have not yet been directly pardoned by the keys of the Church, and which have not been confessed in an individual confession.

This is the complex reality: understanding our sins can be absolved multiple times, in multiple different ways, such that even though non-sacramental paths are capable of restoring us to grace, the law of the Church still requires us to go through the process of individually confessing our grave sins, and obtaining absolution in the ordinary manner. In part, this is to help prevent us from slipping into self-delusion about the authenticity of our repentance; in part, this is to help prevent us from cultivating an arrogant posture of presumption that God will forgive us even if we neglect His sacraments; and in part, this to help us obtain the benefit of the unique graces afforded by sacramental absolution. So in the end, even while our salvation does not rigidly hinge upon the sacraments, there is no excuse for neglecting the sacraments when they do become available to us. We are not permitted to invoke the (possibly true) claim that “God has already forgiven me” as a basis for concluding “therefore I have no obligation to confess my sins in the manner prescribed by the law of the Church”. We are only (temporarily) excused from this obligation insofar as we are impeded accessing from the sacrament by factors beyond our reasonable control.

Nor should it be forgotten that, if our motive for contrition is only imperfect – motivated only by fear, rather than by sincere love of God – even then, that flawed stirring of our conscience must be recognized as a real grace from God: a form of sorrow that (despite its imperfection) suffices to enable sacramental absolution, and can yet be cultivated to eventually blossom into the perfect contrition of charity. Once again, consider the teaching of the Council of Trent, Session 14, Chapter IV:

As to imperfect contrition, which is called attrition, since it commonly arises either from the consideration of the heinousness of sin or from the fear of hell and of punishment, the council declares that if it renounces the desire to sin and hopes for pardon, it not only does not make one a hypocrite and a greater sinner, but is even a gift of God and an impulse of the Holy Ghost, not indeed as already dwelling in the penitent, but only moving him, with which assistance the penitent prepares a way for himself unto justice.

In the end, this is the critical point: if we are acting in good faith – sincerely repenting of our sins (ideally just as quickly as we fall into them) and desiring to confess when the sacrament becomes available to us – then we have nothing to be anxious about. You need only make a sincere perfect act of contrition (being truly sorry for having offended God, not only because of fear of punishment, but above all because we know our sins offend Him Who is all-good and deserving of all our love) to receive the Church’s assurance that God will not hesitate to reconcile us to Himself even before the sacrament is actually received. Even though this doctrine must not be exaggerated or abused through hubris, humble confidence in this truth can be a tremendous weapon against anxiety or despair, and cultivate our love of God’s unbounded mercy.

Fragment 4: Accepting Forgiveness

From “Faith Within Reason” by Herbert McCabe, OP (Chapter 11, pp. 155-158):

Sin is something that changes God into a projection of our guilt, so that we don’t see the real God at all; all we see is some kind of judge. God (the whole meaning and purpose and point of our existence) has become a condemnation of us. God has been turned into Satan, the accuser of man, the paymaster, the one who weighs our deeds and condemns us. It is very odd that so much casual Christian thinking should be worship of Satan, that we should think of the punitive satanic God as the only God available to the sinner. It is very odd that the view of God as seen from the church should ever be simply the view of God as seen from hell. For damnation must be just being fixed in this illusion, stuck forever with the God of the Law, stuck forever with the God provided by our sin.

It is the great characteristic of sinners that they do not know that they are sinners, that they refuse to accept and believe that they are sinners. On the contrary, they have found all the ways of justifying and excusing themselves… and they should not be there at all because they are righteous and virtuous. The desperate boredom of this must be the pain of hell, but the thing that constitutes hell is that God can’t be seen. All that can be seen is this vengeful punitive god who is Satan.

The younger son in [the famous parable of the prodigal son] has escaped hell because he has seen his sin for what it is. He has recognized what it does to his vision of God: ‘I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired servants’ (Lk. 15.21). And, of course, as soon as he really accepts that he is a sinner, he ceases to be one; knowing that you have sinned is contrition or forgiveness, or whatever you like to call it. The rest of the story is not about the father forgiving his son, it is about the father celebrating, welcoming his son with joy and feasting. This is all the real God ever does, because God, the real God, is just helplessly and hopelessly in love with us. He is unconditionally in love with us.

His love does not depend on what we do or what we are like. He doesn’t care whether we are sinners or not. It makes no difference to him. He is just waiting to welcome us with joy and love. Sin doesn’t alter God’s attitude to us; it alters our attitude to him, so that we change him from the God who is simply love and nothing else into this punitive ogre, this Satan.

Never be deluded into thinking that if you have contrition for your sins, if you are sorry for your sins, God will come and forgive you – that he will be touched by your appeal, change his mind about you and forgive you. Not a bit of it. God never changes his mind about you. He is simply in love with you. What he does again and again is change your mind about him. That is why you are sorry. That is what your forgiveness is. You confess your sin, recognize yourself for what you are, because you are forgiven. When you come to confession, to make a ritual proclamation of your sin, to symbolize that you know what you are, you are not coming in order to have your sins forgiven… You come to celebrate that your sins are forgiven.

Fragment 5: Against Misconceptions

Excerpts from “This Tremendous Lover” by Dom Eugene Boylan, OCR:

The question of sorrow is one which is not always properly understood. The sorrow necessary for confession is an act of the will by which through the help of God’s grace we turn away from our sins, resolving to avoid them in future, and turn towards God. The motive must be supernatural; the fear of hell, the loss of heaven, or the love of God are such motives. Since the sorrow is an act of the will, it need not be felt. There are some who have such a lively sorrow for their sins that they can shed tears over them; others have such a vivid feeling of eternal loss that they feel a fear that is greater than any other fear. There are exceptional cases. Most souls, even very holy souls, would feel more sorrow at some painful loss, for example, the death of a parent, than they would feel for their sins. That, however, does not lessen the value of their sorrow for sin in the least. Feelings have nothing to do with it; the real measure and test of the depth of sorrow in the will and the decision to avoid sin in the future. [Chapter 11, p. 135]

Still though our sorrow may not reach the height of perfect contrition, we must not fail to have complete confidence in the generosity of God’s pardon. Provided that we have the minimum sorrow for the validity of the Sacrament, the absolution has its due effect upon our souls; and the grace of God, with the infused virtues of faith, hope and charity – especially that of charity which has been lost by mortal sin – are poured into our soul. This restored virtue of charity gives us the power of loving God again with a supernatural love, and we should strive to awaken the love after confession if we have not been able to do so before it. [Chapter 11, p. 136]

It is of capital importance that we never, never let our past sins – however filthy or treacherous they may have been – come between us and God, or make us in any way doubtful of His love and afraid to approach Him in absolute and intimate confidence. God does not do things by halves. When He forgives sins, He forgives completely. Their guilt is blotted out in its entirety, and He will not reproach us with them again. But His generosity goes even further. When a soul falls into mortal sin all the merits of its past life are lost. If, however, the soul repents and obtains pardon, these merits revive again; such is God’s generosity and love. [Chapter 11, p. 137]

There is always a great temptation to discouragement and distrust even after our sins have been forgiven. We feel that God still holds our sins against us, that His providence will be less favourable to us in the future, that He no longer trusts us not to offend Him again, and He will be reserved and sparing in His graces. We feel too that no matter how great our progress in the future, the ultimate result will always be spoiled by that unfortunate past. The phantom of what might have been had we always been faithful mocks our efforts, lessens our hopes, and disheartens us. There is a certain height, we imagine, which we might have reached, but which is now impossible. All that, natural though it may be, is quite wrong. It is based upon a wrong notion of God and is the result of a failure to understand His power and goodness. It does not matter whether it is the case of a fervent soul who has suddenly given way to temptation, whether it be some sinner who after a life of sin turns to the whole-hearted service of God, or whether it be someone who takes up the spiritual life after many years of carelessness; God can always give us the means to make up for lost time. “To them that love God, all things work together unto good,” writes St. Paul, and St. Augustine would include in “all things” even their sins. It follows then that God can use all things for the good of those who love Him. Even if we conceive of His plan as setting a certain height of holiness for each man, we should also remember that He can lead us to that height from any point we reach in our wanderings. If we lose our way and leave the path He has marked out for us, He can still bring us to the goal by another route. [Chapter 11, p. 138]

…let us be convinced that no matter what we have lost, what we have ruined, or how far we have wandered into the wilderness from the right path, God can give us back all we have lost or damaged. God can show us a road – or if necessary, build a new road for us – that leads from our present position, whatever it may be, to the heights of sanctity. [Chapter 17, p. 231]

With all due respect for my southern hemisphere friends, I am deliberately ignoring the existence of that 10-12% of the human population who live in the Antipodes… not because Saint Augustine considered the existence of “men on the opposite side of the earth… who walk with their feet opposite ours” something “too absurd” to believe without hard proof (then again, maybe that’s fair actually), but purely because your summer solstice is far too inconvenient for the winter-darkness vibe I’m trying to take advantage of here.

Unless, again, you live in the southern hemisphere, where Christians are inevitably compelled to adapt the symbolic emphasis provided by their natural context in a different (but not unrelated) direction: “think[ing] of the long days as a sign of the victory of the light of Christ: ‘The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it’.”