Sources: On Occasions of Sin

"Do not tempt me, Frodo! I dare not take it, not even to keep it safe, unused. The wish to wield it would be too great for my strength." – Gandalf

This is an entry in the Resources series.

Entries in this series will be more dry and technical, not building toward any particular conclusion – but they will also be very useful, laying down and unpacking foundations that will have a wide range of applicability to many arguments in the future.

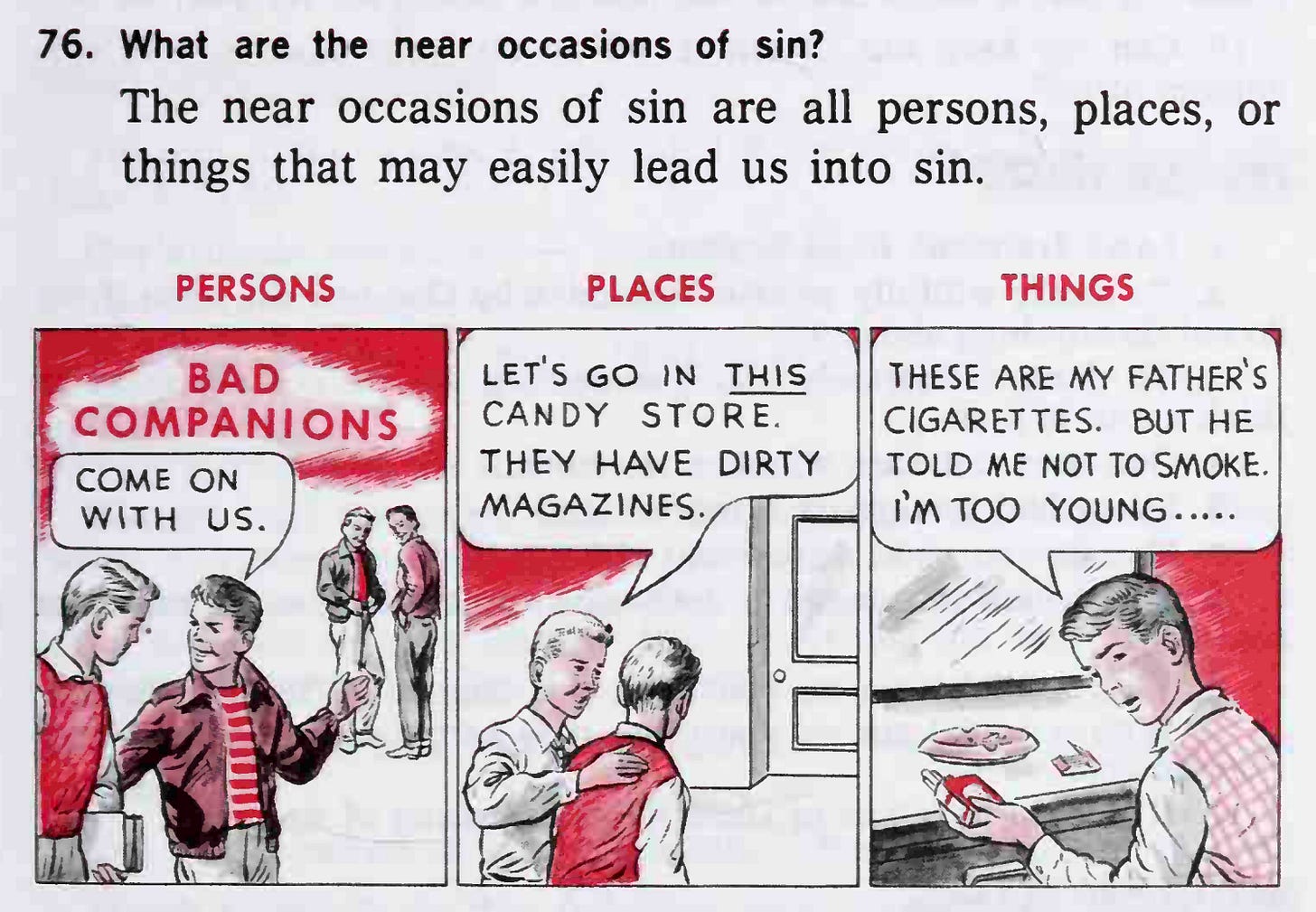

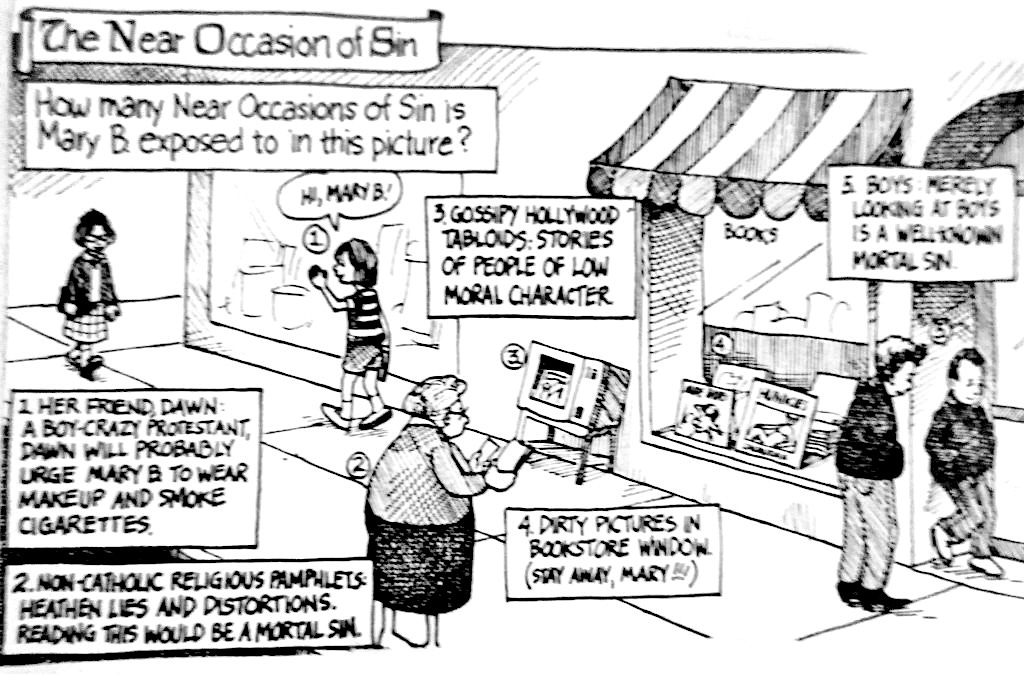

The traditional Act of Contrition includes the resolution “to avoid the near occasion of sin”. This implicitly relies on a distinction drawn by moral theologians between the near (or proximate) occasion of sin, and the remote occasion of sin.

An occasion of sin, in general, is any external circumstance providing an opportunity to sin. But occasions of sin (and temptation) are common in life – and not all occasions of sin involve grave or serious danger. Therefore, our obligation is not to avoid every occasion of sin, but only the near occasion of sin. Thus, in principle: we differentiate between near occasions of sin (where the danger is strong or likely) on the one hand, and remote occasions of sin (where the danger is not strong or likely) on the other. At the same time, in practice: we also recognize that these two categories can exist along a sort of continuum, and at times can even be somewhat subjective.

Surprisingly, the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church does not utilize these concepts. But American Catholics who were raised on any version of the longstanding Baltimore Catechism (1891 text here) will almost certainly recognize this language.

The Catholic Encyclopedia published in 1911 offers a relatively short (but dense) summary of the many distinctions historically developed by moral theologians.

Here below I am reproducing the full text of this particular entry, lightly edited for ease and clarity of reading.Occasions of sin are external circumstances – whether of things or persons – which incite or entice one to sin: either because of their special nature, or because of the frailty common to humanity, or because of the frailty peculiar to some individual.

It is important to remember that there is a wide difference between the cause and the occasion of sin. The cause of sin in the last analysis is the perverse human will... while the occasion is something extrinsic which (given the freedom of the will) cannot properly speaking cause the act or vicious habit that we call sin.

There can be no doubt that, in general, the same obligation which binds us to refrain from sin requires us to shun its occasion.

Theologians distinguish between the proximate and the remote occasion. They are not altogether at one as to the precise value to be attributed to the terms.

De Lugo defines proximate occasion as one in which persons of like caliber for the most part fall into mortal sin, or one in which experience points to the same result from the special weakness of a particular person.

The remote occasion lacks these elements. All theologians are agreed that there is no obligation to avoid the remote occasions of sin – because this would practically speaking be impossible, and because they do not involve serious danger of sin.

As to the proximate occasion, it may be of the sort that is described as necessary, such that a person cannot abandon or get rid of it. Whether this impossibility stands as physical impossibility or moral impossibility does not matter. Or it may be voluntary, that is, within the competency of one to remove.

Moralists distinguish between a proximate occasion that is continuous, and one that (although unquestionably proximate) confronts a person only at intervals.

It is certain that one who is in the presence of a proximate occasion that is both voluntary and continuous is bound to remove it. A refusal on the part of a penitent to do so would make it imperative for the confessor to deny absolution. Yet it is not always necessary for the confessor to await the actual performance of this duty before giving absolution; he may be content with a sincere promise, which is the minimum to be required.

Theologians agree that one is not obliged to shun the proximate but necessary occasions of sin. No one is bound to do what is impossible. There is no question here of freely casting oneself into the danger of sin; the premise is that stress of unavoidable circumstances has imposed this unhappy situation. All that can then be required is the use of whatever means will make the danger of sin remote.

The difficulty is to determine when a proximate occasion is to be regarded as morally necessary. Much has been written by theologians in the attempt to find a rule for the measurement of this moral necessity, and a formula for its expression, but not successfully. It seems to be quite clear that a proximate occasion may be deemed morally necessary when it cannot be given up without grave scandal, or loss of good name, or without notable temporal or spiritual damage.

Another rigorous framework for analyzing occasions of sin can be drawn from Dominic Prümmer’s Handbook of Moral Theology (nn. 709-711).

Dominic M. Prümmer, O.P., (1866–1931) was a Dominican priest, canon lawyer, and theology professor at the University of Fribourg.

Here below I will be presenting the 1956 English translation of Prümmer’s text in a slightly reorganized and lightly edited format, with minimal alterations to the original terminology.Penitents are said to be in the occasion of sin when they are in a proximate occasion of sin. An occasion of sin is any extrinsic circumstance (person, thing, book, play, etc.) which offers a strong incitement to sin and a suitable opportunity.

Therefore: (A) an occasion of sin differs from the danger of sinning... for every occasion of sin is a danger, but not vice-versa, [since] the danger of sinning may be internal, arising from passion or evil habit, etc.; and (B) an occasion of sin differs from scandal (although sometimes the difference is slight), which entices to sin but does not always provide a suitable opportunity.

A remote occasion of sin is one which offers a slight danger of sin in which a person rarely commits sin. A penitent in a remote occasion of sin may be absolved, since such occasions are common to everyone and cannot be avoided.

A proximate occasion is a grave external danger of sinning, either for all persons or only for certain types. The gravity of the danger depends on (a) general experience, (b) the frequency of relapse into the same sin, and (c) the character of the penitent.

The occasion is said to be absolutely proximate if some external circumstance causes a serious danger of sinning for all persons (e.g. reading extremely obscene literature).

The occasion is said to be relatively proximate if it is dangerous only for a certain individual (e.g. a tavern for a habitual drunkard).

A proximate occasion is either free or necessary. It is free if it can be avoided easily (e.g. a tavern); it is necessary if it cannot be avoided (e.g. a minor’s parental home).

A proximate occasion may be continually present if a person remains in the occasion aways and continually (e.g. keeping a mistress in the house).

A proximate occasion is not continually present if a person is in the occasion only at certain times (e.g. a tavern for the drunkard).

Penitents in necessary proximate occasions of sin may also be absolved, if they are truly contrite and seriously resolve to use all the means necessary for avoiding sin. For if the penitent seriously proposes to use the means necessary for avoiding sin, he will conquer his temptations with the help of God, “Who will not allow you to be tempted beyond your powers” (1 Corinthians 10:13).

The chief means to be used for converting a proximate occasion of sin into a remote occasion are fervent prayer, frequent confession, and the avoidance of all intimacy and private conversation with an accomplice in sin. [Note: The modern reader might simply describe this as “setting boundaries” in a relationship where there is some pattern of sin with another person. Those boundaries help make the subjective danger of sin remote.]

Absolution must be denied to any penitent refusing to relinquish a free proximate occasion of sin, for such a penitent is considered to lack a sincere desire of avoiding sin. Generally speaking, one should defer the absolution of a penitent in a free proximate occasion of sin which is continually present, until the penitent has actually removed this occasion… Thus for example, a man who keeps a mistress in his house should not be absolved in normal circumstances until he has dismissed her, especially if he promises to do this in a previous confession and has failed to keep his promise. But notice – in normal circumstances, because there are exceptions when absolution may be given immediately, provided that the penitent seriously promises to leave the free proximate occasion.

Finally, a helpful summary can be drawn from a paper delivered in October 1950, at the 12th Annual National Meeting of the Canon Law Society of America.

On this occasion, Msgr. John Król, JCD, presented his paper titled “Permission to Parties Invalidly Married to Live as Brother and Sister” (subsequently published in the The Jurist 11 (1951) pgs. 7-30) in which he unpacks the complex issue of the so-called “brother-sister arrangement”. This is the phrase most commonly used to describe the scenario of a civilly-married man and woman, who – recognizing the canonical invalidly of their marriage in the eyes of the Church – commit to living chastely, refraining from all sexual intimacy, while still living together under the same roof. They are thus (somewhat imperfectly) described as living “in the manner of brother and sister” rather than living “as a married couple”. (For a vivid example of such an arrangement from the very same era, see the case described here.)

A full discussion of this question is far beyond the scope of this present entry, but a few key points should be highlighted. While laying out the relevant moral principles for occasions of sin, Msgr. Król offers the following reflection:

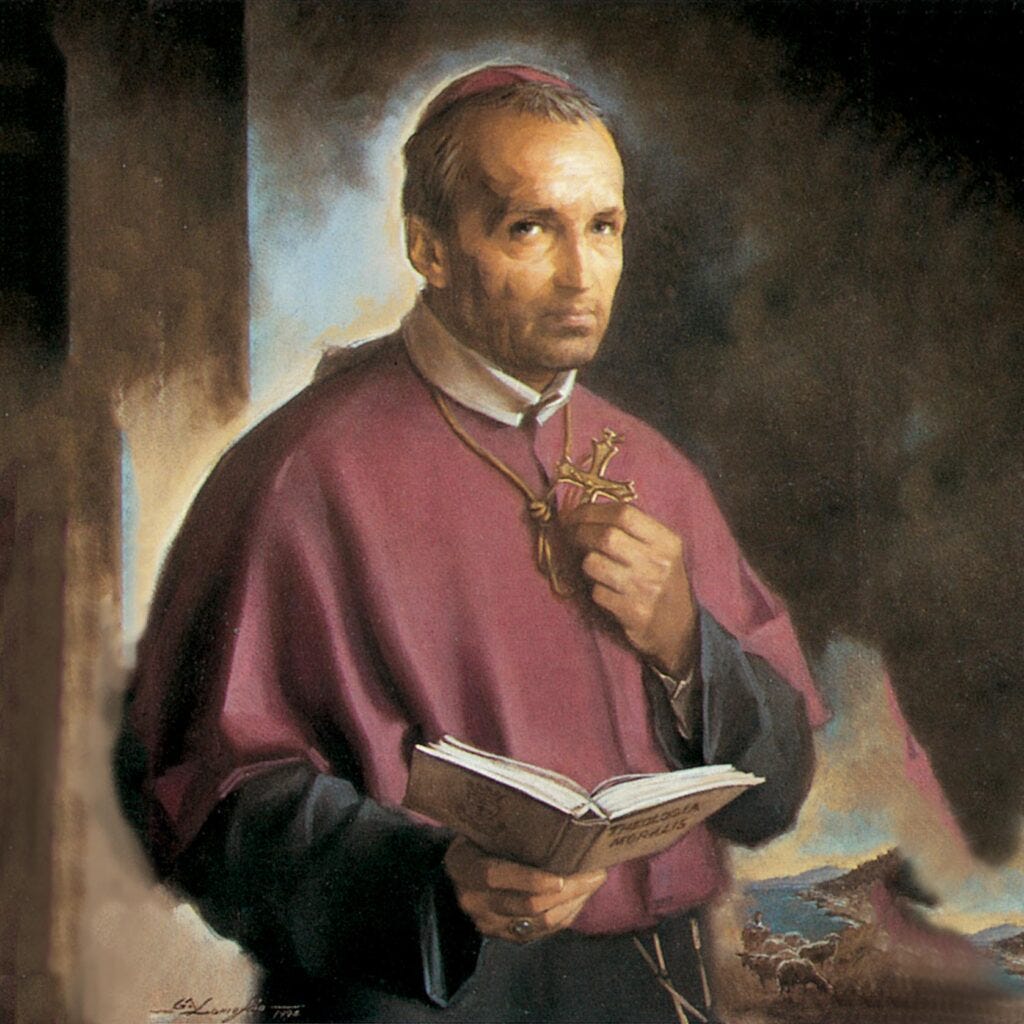

An occasion of sin can be remote or proximate. A remote occasion is one which presents but a slight danger of sinning – in which a person rarely sins. Such occasions exist universally, and they neither can nor must be avoided. The definition of a proximate occasion of sin is a subject of controversy. Many theologians defend St. Alphonsus’ definition of the proximate occasion of sin… [which holds] that even the single occasion of sin must be avoided [when] the danger of sinning mortally is solidly probable. The school of Lugo and Genicot maintains that there is not a serious obligation of avoiding the single occasion, unless the danger of sin is so great as to amount to a moral certainty – as would be had when a situation always or almost always leads one into mortal sin.

While this controversy is of greatest interest to a confessor dealing with the single occasion of sin, we can, in this discussion, completely prescind from it. Our problem is not the single occasion of sin, but a continuous occasion to which a couple in an invalid marriage are exposed. There is no controversy on this point. Even the exponents of the more lenient view agree that one has a serious obligation of giving up the habit of frequenting a voluntary occasion in which [one] often sins mortally. For practical purposes, and particularly to avoid any confusion that might arise from the controversy regarding the single occasion, we must take for granted that as long as the invalidly married couple are in a voluntary proximate occasion of sin, they have no choice except to effect a complete separation.

A proximate occasion is free or voluntary if it can easily be avoided; otherwise it is considered a necessary occasion. The latter can be physically or morally necessary. […] A morally necessary proximate occasion is one that can be avoided, but not without grave difficulty and great harm. [pgs. 15-17]

It is of particular importance to appreciate precisely what, in the opinion of theologians, constitutes a necessary proximate occasion of sin. Ter Haar, who defends the view of St. Alphonsus, provides us with an excellent example. He presents the case of a couple in an incurably invalid union. […] It is rather evident that even the less lenient views of the theologians, who follow St. Alphonsus, make due allowance for the possibility of brother-sister arrangements. [pgs. 18-19]

In this context, Msgr. Król outlines a very helpful summary of the various moral obligations to avoid different types of occasions of sin – effectively distilling the complex web of academic distinctions into a relatively compact five-point list:

From the foregoing, we can, for the purposes of this discussion, deduce the following practical principles:

It is absolutely necessary to avoid any occasion of sin which, in a particular case, is tantamount to sin. If the occasion constitutes a proximate danger to eternal salvation, then, in accordance with the words of Our Lord concerning the plucking out of the eye and the cutting off of the hand (Matt. 5: 29), it must be abandoned even at the risk of one’s life.

It is neither possible nor necessary to avoid a remote occasion of sin. Such occasions exist everywhere for everyone in this world.

A voluntary proximate occasion of sin must be avoided under pain of denial of the sacraments. This is evident from the propositions condemned by Innocent XI [cf. Denzinger-Bannwart-Urnberg, Enchiridion, n. 1212-1213].

Physically necessary proximate occasions of sin cannot be avoided. They must, however, be turned into remote occasions by vigilance and by the use of natural and supernatural aids.

It is lawful to expose oneself to a morally necessary proximate occasion of sin, provided there is a firm and sincere willingness to use the means prescribed to make the materially proximate occasion formally remote.

It must be emphasized that while some theologians defend what is regarded as a rigorous definition of a proximate occasion, they – as well as defenders of the lenient definition – agree that there are occasions of sin which, though normally to be avoided, can be lawfully frequented if [this is] morally or physically necessary. Such, in fact, was the view of St. Alphonsus. [pgs. 17-18]